Two Houses is a newsletter of stories about art, feminism, grief, and Time excavated from the Soho loft where I grew up. Posts are free and illustrated with the work of my long-divorced parents, the painters Mimi Weisbord and Lennart Anderson.

In her loft, my mother’s Rolodex burst with contact cards, dog-eared and leather-soft. On mine, every phone number and address I’d ever had was recorded, including RFD 1 in Underhill before the postal service eliminated the rural route system. Once, I suggested she weed out her exploding Rolodex because it was shedding dead people. She regarded me horrified. I was suggesting she remove a limb.

Now, I see I’m no better. I’m one of those people who saves emails, and they go back more than ten years, some in folders, except Google has preened them. I didn’t know emails could wink out, but at least a few of my mother’s have. This has not been the case with voicemails. I still have her recordings on my phone from when I was scrambling to find her a memory care placement and couldn’t bear playing her angry, paranoid messages. But I also couldn’t erase them. They’re stacked above an earlier recording of her singing to me on my birthday.

In the digital folder labeled “family history,” just one email from my mother remains. I opened it a couple of weeks ago and was surprised by its contents.

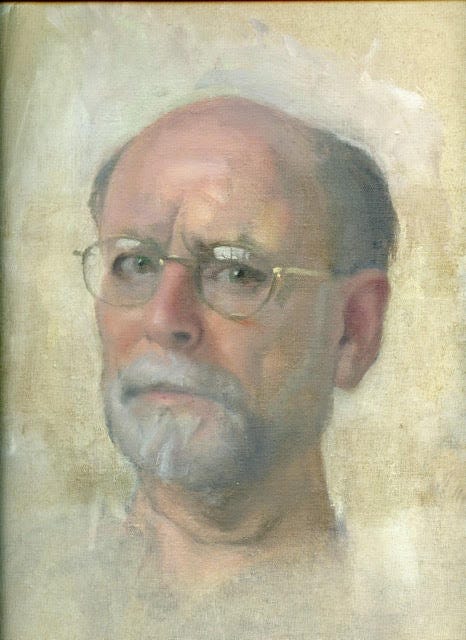

“My drawing of Lennart from 1957. Preliminary to the painting. Collection of Eugene Carroll.”

Eugene Carroll was an old friend of my parents from the American Academy in Rome. He had a fellowship in 1958, as did my father. An art historian of the Italian Renaissance, Eugene taught at Vassar College for decades. Mimi and Eugene adored each other. She once quipped that if he’d not been gay, she might have ended up with him.

The email is from 2014. A year later, my father died, and we held a memorial for him at the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Eugene made the trip into the city.

My mother was ecstatic to visit with Eugene. His attendance took great effort; his health was so poor. After the speakers concluded, she stood beside the bench where he sat, distinguished and ruddy-faced, clutching his cane beneath the blinking slide show of my father’s life. My mother, at 80, was positively girlish in his presence.

I had wanted to include my mother’s painting of Lennart in that memorial slideshow. I’m unaware of any other portraits of Lennart Anderson besides his self-portraits. But the decision was to include photos only and no paintings. The drawing isn’t a great likeness, but the painting is gorgeous. I share it here often.

The poet Honor Moore once told me this painting reminds her of work by the German Renaissance painter Lucas Cranach. With a few strokes at my keyboard, I found that email among my thirty thousand messages. She provides a Cranach example.

I see what she means. The tones and a certain flatness (also characteristic of my mother).

As his daughter, however, what most strikes me about Lennart’s portrait is his tender seriousness. I know that earnest patience. He was 29 years old when Mimi painted him, but he carried that look right to his end at 87, maintaining that steady forbearance.

Lennart was very much alive when Mimi passed this painting on to me, however. What amazed me then was learning he’d ever sat for her. (And that she’d ever painted portraits!) The painting is a vestige of a companionship between them that I never knew. I was four when they announced their separation.

Eugene Carroll, who owned the drawing, was also a hoarder with various collections, including my mother's art. Years after he died, my mother also gone, his art was auctioned. I watched my mother’s paintings surface in an online listing and then vanish, probably unsold. It was painful. I could not preserve any more of what I already struggled to protect, though it haunted me to see some of her work go unidentified (her fault for not signing them). Lennart’s work was also in Eugene’s collection. They were there together, my painter-parents.

His paintings included wonderful heads of Eugene.

Eugene emailed the portrait below to my mother after learning of Lennart’s passing in 2015. She forwarded it on to me and my brother.

This portrait was also auctioned from Eugene’s collection.

Lately, I am reveling in my digital hoarding, though I now pay Google $20/year for the space to preserve it. While writing this piece, I searched “Eugene Carroll” in my inbox. Up popped another email from my mother, this time with an attachment, her voice and perspective rising from the ether.

She shares what she planned to read at Eugene’s memorial. (He died in 2016.) And she revels in her hoarding.

Here is that eulogy, lightly edited, bolded as she had it, and illustrated with photos from the loft.

I met Eugene in the Fall of 1958 at the American Academy in Rome. He was 28 and a new Rome Prize winner, and I was five years younger, recently out of art school, and newly married to a Fellow in painting. The three of us hit it off immediately, and how lucky for me because Eugene always lit up my life.

These days, not a day goes by when I don't think of picking up the phone to check out something with him—an exhibition, a painting I need to discuss, a restaurant he would like, but most often something humorous he would find funny too.

There were years when we lost touch, but when we rediscovered our friendship, he insisted that we celebrate our birthdays together again (the June dates were very close), and reminiscing about our good times in Rome became more and more important.

There were those horror movies and Marguerite Duras films dubbed in Italian at our local Gianicolo movie house. Because we dined at eight, a small group of us would have to wait to trudge off to the eleven pm show at the Del Vascello. But Eugene would insist on arriving at ten-thirty so we could improve our Italian by watching the toothpaste and laundry soap ads on the large screen before the main feature.

And we loved remembering the eccentrics or bizarre events at the Academy, like the wonderful Sunday dinner at a restaurant in Rome with our group of friends, when the communal pile of “lira” mysteriously disappeared from the table before the “conto” was paid. We never tired of speculating about who did it.

Back in the States, Eugene would visit. He gamely stayed at our loft by the Fulton Fish Market when the first child was born and even amazingly arranged for my husband to babysit one night so he could take me to a movie, giving me a break from motherhood. A few years later, he pulled up to our summer house in rural Western Mass, looking totally dashing with his new convertible, and whisked me off to tool around the countryside looking for antiques. His thank-you note sent regards to our “lucky-go-happy” children.

The other day, I found a letter from the 1970s, thanking me for inviting him to my husband's opening and dinner, where he was seated next to Erica Jong, a poet friend of mine at the time. He was ecstatic about meeting her and extolled the great company ... but he thought he might owe her an apology for having compared her to Ginger Rogers.

I read the old letters and emails, and they make me happy. I can hear his voice so clearly. We were always laughing about something. We 'got' each other, as he would say. Recently, looking at a photo of the three of us all dressed up for a cocktail party in 1960s Rome, Eugene wistfully remarked, "We were at the height of our beauty."

Last year, when we celebrated our birthdays, he was 85, and I was still five years younger. And not a day goes by when there isn't something I'd like to share with him and listen to his elegant and amusing take on art, literature, and life. Others can speak of his scholarship, his dedication to his work, and his professorial skills; I can attest to his generosity in supporting the work of others and his gift for friendship.

The last time I saw Eugene was at my former husband's memorial; he had predeceased Eugene by some months. They had forged a lifelong friendship, and Eugene had made sure he got there to say goodbye—to both of us, as it turned out.

So, dearest Eugene, I wish you were here. But wherever you are now, I know you're making the most of it. As for me, I can still hear your voice and feel your presence, and I will never again pass through Grand Central Station without seeing you slowly and haltingly come down the ramp with your walker and your funny hat and ancient jacket, your subdued and expectant smile, looking forward to all the fun we’d have together.

What treasures have you found in your inbox? Do you have a great hoarding story? Leave a comment! I love hearing from you. And please hit “like” (the heart symbol below) to help others find my work.

So much here is rich and wonderful to see, especially the paintings, the comparison to Cranach's portrait of Martin Luther, and the glamorous young photo of Mimi and Lennart. But what moved me in the deepest way was reading Mimi's eulogy for Eugene and thinking of her enduring care for a friend. And did I somehow not know what good writer she was?

So much of us is retained in things - art - songs - scars and all that caused them. Time's a strange fish. Thank you for this fabulously resonant post - I identify - my mother's mother's things still stashed in trunks and spilling death.