Hundreds of Drawings Turn Up by My Father, Lennart Anderson

Better title: “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” - after Delmore Schwartz

Two Houses. Two Painters. Two Parents. is a newsletter of stories about art, feminism, grief, and time excavated from the Soho loft where I grew up. Posts are free and illustrated with the work of my long-divorced parents, the painters Mimi Weisbord and Lennart Anderson. Sign up here:

My half-sister Jeanette is selling the brownstone where we grew up in Brooklyn. (I don’t know why.) Hundreds of drawings have surfaced in the process, work by our late father, Lennart; many figures sketched while teaching, but other works, too, including drawings he made of Mimi, my mother.

This one is framed.

Studying this photo, I feel a tug. The drawing is familiar. Did it hang in the house somewhere before all the dismantling that comes with the end of a marriage? I was four when they announced their impending separation and five when my mother moved out.

How can I remember this drawing when my father put it away to forget?

Since the election, the writing I do here seems irrelevant and indulgent. It brings to mind a time in 2020 when, three weeks after my mother’s death, the nation suffered another historic inflection point: George Floyd’s murder and the protests it ignited. History lurched forward without my mother, oblivious, making her tiny (I wrote in my memoir), revealing time as a tangible physical property, roaring forward on its rushing current.

Why should anyone care about my life with my parents? Since the election, I know I’m tiny, too.

I don’t have an answer.

I do know that in the four years since my mother’s passing, the starkness of her absence has faded. Time is doing its job. “With Time” we say, “with time, it will lessen.”

Yet we are always with Time, and still, Time baffles. It may or may not heal. It’s our biggest head trip, this making sense of Time.

Lately, I dream of living abroad. My parents lived in Italy for three years. My mother also traveled extensively during the last third of her life. In both eras, she loved Hydra, an island off Athens.

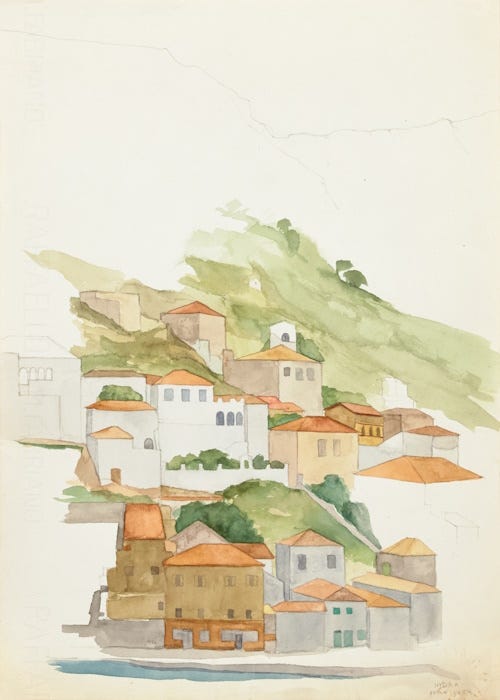

In the loft, after she died, I found a Hydra watercolor by her dated “May 1959.”

History rushes forward with the election, but I am pulled backward. Some of the work found by my father takes me again to Hydra in 1959, where their lives and art overlap. Who will care?, I hear myself asking.

The four-year-old I carry inside answers.

I do.

My four-year-old is insatiable and wants to know everything: how they came together and how they blew apart with enough energy to expand their chaos indefinitely.

Once, in the American Museum of Natural History, Dad sat on a bench with me in the exhibit on the origin of the universe.

We met there rather than at the house in Brooklyn because I was estranged from his second wife, Barbara. And because my partner Kim was interested in astronomy.

As Kim read everything on the walls, my father absorbed the astronomical evidence (and perhaps why I refused to visit his house any longer?).

Eventually, he said simply, “Where does all of this leave Rembrandt?”

Four-year-olds ask questions no one is prepared to answer.

What is death?

What is love?

When my half-sister Jeanette was four, she asked me and Kim about love.

One morning, full of curiosity, she crawled onto the futon where we were sleeping in the middle of Dad’s cabin in Maine. We received her joyously.

I don’t remember exactly what we’d said, but the moment set off her mother.

Boom.

Barbara communicated with body language, her rage filling all the spaces.

Eventually, she explained we had exposed Jeanette to an “uncommitted relationship.” (This was the era before gay marriage.)

Jeanette should know only that Kim and I were friends.

My father loved Kim but said nothing. (We slept in a tent on the lawn after that.)

Eventually, she declared a compromise. “I don’t care what Jeanette knows. I just don’t want to have to be the one to tell her.”

Time would prove she didn’t mean that either.

(Lennart was a great observer of figures he’d bring together.)

Barbara was nine years old and living on Staten Island when my parents were painting, drawing, and eating fish on Hydra.

When Jeanette was nine, Kim and I held a commitment ceremony in Vermont.

Barbara pretended to be a designated photographer, hiding behind her camera, under tents, peeking from behind bushes. We never saw a print. (Was there film in her camera?)

Jeanette took the best pictures that day. Children inspire smiles and open hearts, and her photos capture the warmth of our guests as they receive her.

On Hydra, in 1959, Lennart was 30, and Mimi was 23. This is the loveliest place imaginable, my mother describes in a letter home on Easter Sunday. I’ve quoted this passage before:

—the houses are built on the sides of hills that form a semi-circle around the bay. The sea, the Aegean, is the bluest, greenest I’ve ever seen, and the sun is fantastically bright. [...] There are no automobiles or Vespas as there are no roads and few streets. Mostly steps going up, up to the houses. Lots of donkeys, though, and goats and cats and things. [....] The halvah here is out of this world—also the oranges, octopus, and goat's cheese.

Since her death, Greece is for me, twice mythological.

I imagine my parents there, in the afterlife, eating fish.

The little me likes that idea. Yes, put them there!

They’ll fight, I answer her.

Not back then, she argues. They were happy.

It’s not entirely a fantasy.

In 2019, the year before my mother died, she sent me to Chinatown for takeout. She hoped I’d bring back a whole fish to share.

I mentioned that Dad used to always want me to share a whole fish with him at Chinese restaurants.

“It’s because of a bream we ate in Greece by the water,” she explained out of nowhere.

A wave of loss lapped over me.

(The bream I ate on Corfu in 2023 was incredible.)

After my parents’ deaths, I learned that Kim’s and my commitment ceremony took place on a date in 1998 that was one day shy of what would have been my parents’ 40th wedding anniversary.

Only after my mother died did I understand Time’s warped sense of humor.

Now, I fear Time’s echoes and returns. I don’t yet know how to occupy my skin for the dark days predicted post-election. The raft that pushed off from the mainland of life with my parents feels very much further out to sea.

Writing allows me to imagine them where it is forever 1959. I can extend that meal where they sit on the edge of the Aegean, a bream between their fingers, the tender flesh falling off delicate bones — a moment that should never have ended.

Stay, I want to tell them. Paint. Capture and suspend the light. Barbara can stay put on Staten Island. I’ll remain raw energy in the universe. Stay where there are no cars, where nothing changes, as in a painting, where the day prevails. Your paintings are your children.

Wow. Eliza. Wow. I am so deeply impressed by your clarity and bravery.

You are the best kind of badass❤️

The ending of this post is perfect, Eliza, telling your parents to stay, to let their art be their kids--so poignant, in that it's both an acknowledgement of their early happiness and success, particularly the potential in your mom's career at that time, and a condemnation of their future parenting. Really well done. And powerful.