Minimalism

Drawings by the minimalist sculptor Fred Sandback turned up in the loft. Then I found the story I wrote in college about the relationship he had with my mother ...

My mother, Mimi Weisbord, had a relationship with Fred Sandback in the late 1970s, a few years after she left my father. In 2021, I found prints and drawings by Fred in her Soho studio, also his show catalogs, letters to my mother, a journal with sketches, and the start of a novel about their relationship that she never completed. Below is a piece I wrote during my sophomore year in college — edited, annotated, and illustrated — another window on divorce.

Fred

Panda Bear was a three-inch Steiff panda who sported a second fur coat and drove a yellow tin automobile. The letters I received from him were always in perfect business format, signed with a paw print, and addressed to my two miniature monkeys.

“My Dear Monkeys,” they would begin. “Greetings. I hope this letter finds you well and prosperous.”

Panda’s sophistication, vanity, and feigned knowledge of the art world were the fabrications of my mom’s boyfriend, Fred. One letter went on like this:

As you may know by now, my agent has deposited a work of art with your agent for your inspection. You will surely recognize this composition as the work of Bibeau LeBreton. It is documented in Emmet Jeffers’ “Lives and Times of the Winchendon Floralists,” a study for Bibeau’s masterpiece, “Big Flowers.”

Under the circumstances (and, of course, considering the bottoming-out of the banana market), I feel that you must be willing to surrender a Prime Florida Grapefruit for this work. It seems a risky investment now, but I can assure you that your courage will be richly rewarded within the decade. I applaud your perspicacity as serious collectors of the Winchendon Floralists.

In parting, I pause to muse on the words of the great Tintoretto: “Flowers are so pretty!”

Yours in Mammon,

Panda Bear

Fred had found this bear, and his son Peter had made it the fur coat. The bear, car, and all appeared in my room just shortly after Mom started seeing Fred.

I kept them for decades. I found them in our barn in Vermont about the same time that I found this essay.

Mom didn’t need to “sell” Fred to me and my brother Orrin. We liked him from the beginning, and she knew it. Our tolerance must have been a relief because I didn’t have a track record of good behavior when it came to the men she dated. Once, in a Chinese restaurant, a younger man gave her his phone number and said, “We can see if we like each other.” Horrified, I thought I’d do her the favor of getting rid of him. “Do you have any idea how old my mom is?” I still haven’t lived this down.

Fred was younger than Mom, too, but he wasn’t a stranger. I had gone to nursery school with his son Peter in Brooklyn and to the same summer camp in Vermont as his daughter Annika. I even had a dim memory of my family visiting his family at their summer place in New Hampshire before “the divorces.”

For a time, he’d even lived on our block in Park Slope while my parents were still together.

What endeared me to Fred was his sense of humor. When I brought to his loft a blonde wig that a friend gave me as a joke, Fred put it on his teddy, declaring, “Dolly Parton Bear!”

It seemed funny to me that Fred had a teddy bear at all. He towered above Mom and had a bushy red beard, a ponytail, and a bit of a pot belly. I had a hard time imagining him crouched over a typewriter, picking out Panda letters to me.

No wonder we loved him.

Mom’s humor also blossomed around Fred. She’d say our ’72 Volkswagen was having an affair with Fred’s blue Ford pickup. “Oooh, Volksie’s so happy!’ she’d gush. “She’s parked for the whole weekend behind Big Blue.” Or “Big Blue is jealous because Volksie got a spot between an attractive little Italian number and a shiny red van.”

They were always parking and re-parking. That was life with a car in Soho.

The year Mom and Fred started seeing each other, Orrin was in his first year of high school, and I was in the sixth grade. Fred was renovating a loft in the old Singer building on Broadway, and Orrin and I would often go over there after school. This was easy because his loft was just a couple of blocks from ours on Lafayette Street. It was so close that at night, we could step out on the roof of the adjacent building and see if his lights were on.

She was obsessed with his lights after they split. Was he in town? And — I’ve learned from her journal — who was with him?

At Fred’s, Orrin and I would hang out and play ping pong while he and Mom worked on renovating his loft. Weekends were the most fun because his children, Anni and Peter, might be there. Sometimes, we would sleep over, Orrin in Peter’s room and I in Anni’s.

It feels transgressive to write about their father. I haven’t seen them since this time.

Anni wasn’t around as much as Peter; she was older, and her life had a wider scope than ours. Peter’s presence meant another marker on the board game and better hands of Go Fish.

I don’t think we saw them as much as I suggest here.

I don’t know how they felt about our parents together. We never talked about any of it. Even on my own, I hardly thought about the future. Though, I do remember asking my “Magic Eight Ball” if Mom and Fred would get married. I’d shake it over and over until its answer came up yes.

In Brooklyn, my mother used to slip into my room to ask it questions, too. In Manhattan, Clapton’s love song, “Wonderful Tonight,” became her soundtrack.

Orrin and I didn’t talk about our feelings for Fred, but when Fred and Mom took a trip to Puerto Rico, Orrin hugged Fred goodbye, startling everyone. For the most part, Orrin and I showed Fred little affection, and Anni and Peter showed little to Mom.

We had all been through divorce.

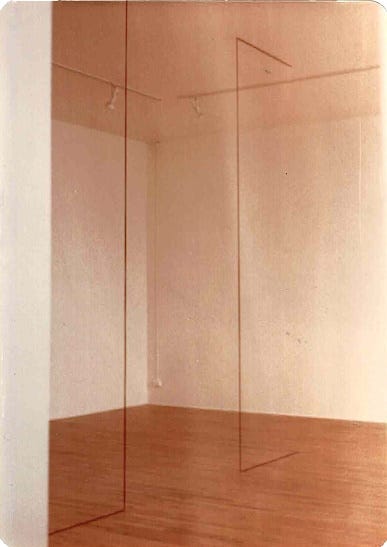

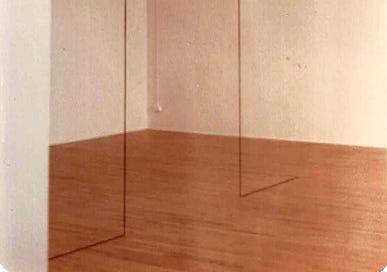

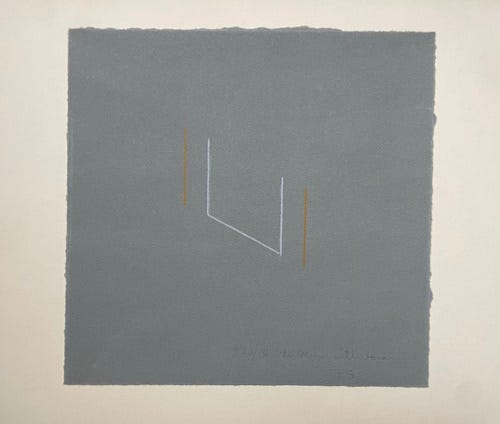

Fred was renovating a loft for the same reason other artists did — the space would let him work on big projects. Fred could live comfortably in the old Singer building, have his kids weekends, and still set aside a big space for his sculpture. After school, I’d find yarn strung from the floor to the ceiling and back again in different angles. This was Fred’s art.

In a Sandback catalog from 1975, I find inscribed: “to Mimi, my friend and teacher.”

Mom was in her “linoleum period.” She took vintage linoleum patterns and reproduced them on canvas floor cloths. She painted a floral linoleum pattern on our coffee table, and while Fred was building the kitchen and bathroom of this loft, she was busy sanding and prepping his dining room table for a similar pattern.

My mother thought moving to Soho was the launch of her life with him, this handsome artist who respected her work. I was stunned to learn this from her journal and that their relationship had started in Brooklyn.

Mom would go to any length for a new pattern of vintage linoleum. Once, I stood waiting on a traffic island while she tried to pick a piece out of warm asphalt on Park Avenue.

She also collected vintage textile and wallpaper patterns. She traced this passion to drawing on wallpaper with a crayon, her first childhood memory.

Maybe it was because Fred had such a good sense of humor that I had a hard time taking his work seriously. A show of his would consist of five or six yarn "sculptures." I used to bug Fred by plucking at the yarn like a harp string. One time, I asked him what he'd do if I just snipped it. "I hate it when people do that," he replied.

He made us all laugh. I loved seeing my mother so happy.

To me, art had always been something a person made that couldn't be duplicated. No matter how bizarre a form of art had been, it was always something that looked as though it had taken a great deal of thought and time. I was astonished Fred was considered a genius in places like Sweden and Germany and had a show up at MOMA. I was also surprised that this kind of art had a name: "Minimalism."

In hindsight, such austere work from Fred feels strange. He listened so well. His warm eyes held onto me.

I tried to make sense of his success. I asked Orrin what it was all about. "It has to do with the subdivision of space," he said. “It suggests divisions to people.”

Mom painted vintage patterns as a way of preserving and transforming them. Fred’s work was referential of nothing. “Simple facts,” he called them.1

Orrin drew and colored with graph paper, creating his own abstract designs. Fred encouraged him with a roll of high-quality "rag" graph paper. When Fred came over, he sometimes sat and talked with him about it. Once, after Fred left, Mom ribbed Orrin that he'd talked Fred's ear off. "No, I didn't!" he protested. And then, "Did I?"

Dad didn’t ask questions and listen like Fred. Not in those years. No one did.

Fred, Anni, and Peter spent the Christmas of 1978 with us on Lafayette Street. Mom and Fred saved money by buying just one Christmas tree, which Fred named “Ralph.”

That was the Christmas when everything began to unravel.

Although we spent Christmas together, I was growing apprehensive. Mom had begun talking down Fred, complaining about this or that in his personality, his irresponsibility.

He seemed lost about the holiday. The presents he’d wrapped for Christmas were stolen from his truck left parked on the pier. I’d forgotten that until I read her journal, and it all came flooding back.

Her anger was hard to take. I could tell her to stop when she’d complain about my dad, but with Fred, I knew that my loyalty belonged to Mom. So I’d listen and pretend to sympathize

and retreat to my room, where I’d dread her heavy tread down the hallway. Deep down, I’d always known it would end this way.

One night, I was sleeping in Anni’s room and got up to go to the bathroom. I found Mom and Fred having it out in the kitchen. I remember thinking how ridiculous they looked, five-foot-four Mom yelling up at six-foot-something Fred. Hearing them reminded me of when I was little, and used to listen to my parents fighting. I would get out of bed and sit on the stairwell, listening.

Then, one night, I slept over at Fred’s without my mother. Another woman was staying over, a woman much younger than Mom. I was confused about who she was, why she was there, why I was there. My heart hit my stomach when I spied Fred in a short robe with his guitar. I don’t know if I told my mother. But in her journal, she knew and was upset that he did that with me there.

Still, I didn’t anticipate their splitting up, even when with their fighting came long, serious phone conversations.

Always, I minimized their problems.

Most of our loft is built with open partitions, so these conversations took place in the bathroom, the only room that’s even close to being soundproof. Orrin and I knew that Mom and Fred were in a deep discussion whenever the phone cord could be traced through the laundry room and under the bathroom door.

The most indelible of these memories: the “simple fact” of this trailing phone line.

Then came the day Mom emerged from the bathroom, “Kids, Fred wants to speak to each of you. But I think we’re going to be able to work things out.”

I don’t remember much of my conversation with him. Mostly, I recall him telling me there was still a chance they’d stay together. They each spoke as if they were waiting to see how the dice would roll,

as if the Magic Eight Ball had yet to reveal its answer.

Two nights later, the verdict was in. Mom said Fred wanted to talk to us again. When it was my turn, I walked into the bathroom and found Orrin crying into the phone.

Stunned, I sat on the edge of the tub in silence, holding the receiver while Fred cried and told me he loved me, that it was all his fault, and that he was sorry.

Fred’s letters take full responsibility for their breakup. His problems were old and ran too deep. One letter is addressed to me and Orrin. He says he hopes we’ll still see each other on weekends and still go camping that summer. In a letter to Mom, he says he doesn’t know if writing that to us is appropriate; she’ll have to decide whether we should have it. I think we did see it at the time.

Over the next few days, I listened to Mom go on and on about how their break-up was all Fred’s fault. It felt like she expected me to be as bitter toward Fred as she was. I wondered if I was supposed to feel whatever she felt toward him.

She veered between sounding still in love with him and sounding enraged.

Part of me thought, yes, it was my duty. But another part of me hurt because of the things she’d say.

I was supposed to love him only when she loved him. In college, my therapist explained to me about “boundaries” and how my mother didn’t have any.

Orrin didn’t listen to Mom. He didn’t tell her to stop, but he also wouldn’t respond. I listened, maybe because, at least this way, Fred hadn’t completely faded out of the picture.

At school, my two best friends, Glynis and Anita, were the only people I let know how strongly I’d felt about Fred and Mom together. Still, when Glynis offered me sympathy, I said, “It’s no big deal. He was just a boyfriend of Mom’s that didn’t work out.”

That’s all there was room for, and I shrank to fit that space.

“Many of Mr. Sandback’s works hover between absence and presence,” observes a critic for The New York Times2.

Eventually, Orrin told me what happened the day after our last phone call with Fred. Orrin and Mom had gone down to the gourmet deli to buy breakfast to make us all feel better. On their way, they saw Fred and Peter walking toward them on the other side of the street. Fred looked at him, raised his hand, and twiddled his fingers as though to say, “I’m sorry, Orrin.”

Six-foot-something Fred twiddling his fingers in the air.

When Mom and Fred broke up, they returned each other’s belongings. And I remember her complaining that he returned things she’d given to him as gifts.

Her anger was mixed with so much grief; I didn’t understand it. Then, I found a handbound book of her floral patterns inscribed to him. He gave her back everything — even her work — his loft always so spare.

Looking back, my relationship with Fred didn’t end like Mom’s. I never got back Dolly Parton Bear’s wig.

And I kept the yellow tin car and Panda Bear.

Fred Sandback from Plan & Space, exh. cat. (Gent: Koninklijke Academie, 1977).

Johnson, Ken. “Fred Sandback.” The New York Times, 7 May 2004, www.nytimes.com/2004/05/07/arts-in-review-fred-sandback.html

There is so much love for Fred in your writing--then and now--and the connection between the themes of his art and the themes in your writing (the line between absence and presence). Beautiful.

‘I was supposed to love him only while she loved him.’ That is such a telling sentence.

Also that comment you made when they were first going out, “Do you have any idea how old my mom is?” Made me laugh out loud, Eliza. But ouch!