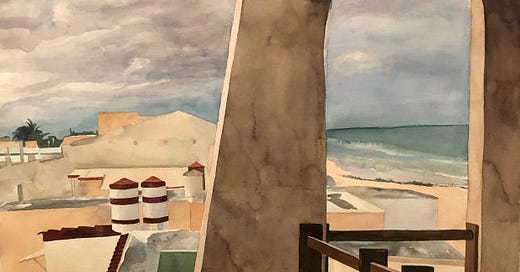

Two Houses is a newsletter of stories about art, feminism, grief, and Time excavated from the Soho loft where I grew up. Posts are free and illustrated with the work of my long-divorced parents, the painters Mimi Weisbord and Lennart Anderson.

The plan was to enjoy a meal together. The plan was always to enjoy a meal together, starting in the loft at Thanksgiving in 2018 when we had to clear off the dining table to find it and carve out space on the kitchen counter to cook. To be fair, those circumstances weren’t particular to my mother’s dementia; for years, her things had encroached like a rising sea. Even in my childhood, at the apartment in Brooklyn, I can remember asking if we might regain our table for my birthday cake. I must have been about eight years old. She guiltily agreed, clearing off stacks of papers, books, and watercolors. It’s touching to look back on and find I’d ever had that sway.

In 2019, Thanksgiving would be at her assisted living place on Long Island, and she was disgusted with my spouse, Kim, and me for not bringing an entire holiday meal from Vermont. She had loved the meal we’d cooked in the loft the year before, though I think she loved the cleared table more. Afterward, on the phone, she told me she’d been polishing it, hoping to attract friends to join her for leftovers. No one came.

To visit was to witness the rising tide. A tragedy of excesses: too many purchases, plans, and words tumbling and roiling as she’d order us around. When we came to help, she had me cleaning dust behind the refrigerator, lining bathroom drawers with contact paper, soaking labels off empty Advil bottles; nothing to be discarded. As sea level rose, her island grew smaller until she was stuck and angry on her little patch of ground.

At her assisted living residence, we arrive to join her in the elegant private dining room. Here, the residence often tucks us away with a white tablecloth and men who serve us in tuxedos, bringing coffee, non-dairy creamer, and sugar-free everything.

But this time, she hadn’t left her room in days, and when she rolls into the wide empty hallway, she is like a newborn just unswaddled, arms and legs flying out from her wheelchair. She cries in the elevator and, arriving downstairs, fixates on the glass French doors in the dining room. She is concerned with who might come through them (with everyone plotting against her).

I soak in her desperation (an old habit) and grab my phone for a distraction. I want to anchor her with a recording from the past. I want our visit to amount to more than watching my mother wash out to sea.

“Brittle-boned, thigh deep and/Wading bird-like my father stood,” begins the poem “Undertow,” read by its poet Verandah Porche, streaming from my phone. “While ocean spit and bat the beach about.”

“Undertow” tells the story of a day when her parents nearly succumbed to the surf.

My mother produced this recording of Verandah Porche in 1972. I’d found it online, archived by Pacifica Radio station WBAI-FM. Finding it was thrilling. Kim had met Verandah at a conference, and together, they’d discovered this half-century-ago connection. Verandah told Kim how my mother encouraged her as a young poet. In 1972, she had included Verandah on her radio platform “Women Poets Reading” alongside poet-greats Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich. She also brought Verandah to Joan Larkin’s for a book launch or a poetry reading.

Now, at this elegant dining table, Veranda’s youthful voice, age 26, cuts through the decades with an old soul’s cosmic prescience.

[...] Ocean pulls the sand against each step. Salt-blind and tripping, Mama loosens her grip. My father floats between her arms, Surrendering limp and fading To the seaward thrust.

I’m watching my mother. I’m oblivious to this poem’s themes. I’m poised and anxious, prepared for her to demand that I stop the reading.

But I want to answer the question that each visit hangs in the air. Can my mother surface? (Is she still in there?)

If I’d known this poem’s subject, I’d likely have avoided it. (Frail parents in the surf?)

Looking back, “Undertow” feels just right.

The poem casts mortal aging and its struggles in Greek mythological terms. The poet’s mother (who is “no Circe’) tries and fails to rescue her father (“Perseus”). Lifeguards succeed. Heroic frailty is twice washed in love by a mother’s efforts and a daughter’s tender recounting.

The poem concludes with her father at home, “Ear, like a sea shell/Pressed to the pillow,” safe in bed but still vulnerable: “The undertow, swirling about him,/Glides my father to sleep.”

Settled in the dining room, my mother’s eyes — large, dark, sunken orbs — dashed about the table where she rested her long fingers. But when this poem launches, she stills and stares silently at my iPhone resting on the table.

I hold my breath as she begins nodding to the poem’s rhythm.

“It was so important for people to hear Verandah read,” she explains. “It made a big difference for her. I knew it would.”

“Undertow”

(reproduced with permission) Brittle-boned, thigh-deep, and Wading bird-like, my father stood While ocean bit and spat the beach about. The sun bled on his back Worn pale from years in hiding. Now bronze and mole-speckled, He watches the water leering-- Black, unloving mirror, Unlike Mama's eyes, which tempered To near sight, no longer see-- Gorgon, unsparing, mocks in a whirlpool, Eye, shoulder, elbow, torso, Perseus, my father. No Circe, Barebacked seahorse woman, Mama paddles porpoise-like, No Aphrodite, Wet skirt clings to her billowing thighs, Perhaps a second cousin to the sea, She muses. Above, the sun and moon Divide the sky. Late afternoon, The ocean eats her young. Caught in the throat Of a gigantic inhalation, My father topples, Groping, crippled, for Mama, Whose arms around him lug him Trembling, toward the shore. Ocean pulls the sand against each step. Salt-blind and tripping, Mama loosens her grip. My father floats between her arms, Surrendering limp and fading To the seaward thrust. He didn't drown in the mouth of a wave. Nine long lifeguards Answered Mama's shrieks. Rushing from their canvas chairs, They linked together Elbow, shoulder, And waded To the place where my father floated Numb and faceless. They towed him back. Safe in a home of bathtubs and seascapes, Mama mails the postcards She forgot to send. Weary from an evening of crosswords And comedies, My father climbs the stairs. Reduced to underwear, Suntan fading, He puts himself to bed. Ear, like a seashell Pressed to the pillow, Hears the thrash and babble of a wave. Blankets sprawl around him Wrinkled like ripples. Eyes folded And falling, The undertow, swirling about him, Glides my father into sleep

Verandah Porche has three volumes of poetry, including The Body's Symmetry (Harper and Row, 1974), which includes "Undertow.” Verandah works as a poet-in-residence, performer, and writing partner from Total Loss Farm, the Vermont commune where she has resided since 1968. Among her awards and honors are the Vermont Arts Council's Award of Merit and Ellen McCollough-Lovell Award.

Dear Eliza, I love how you wove this together. When she heard my voice, Mimi remembered what she gave me. A lucky opening. Love to you and Kim. Verandah

"I want our visit to amount to more than watching my mother wash out to sea."

I found this so moving, Eliza. The significance of clearing the table. Always such a source of anxiety in my own childhood home right through my life. I felt like every time we cleared it, the tide just came back in.

Also, the connecting through poetry and the theme of the poem.

A week before my mum died, she was in a nursing home and her memory was failing, but while I held her hand she spoke, word perfect, several stanzas of Horatius at the Bridge, a poem she'd learned off by heart when at school.

And the poem you chose to read to her, about the undertow, reminded me of almost losing my dad when, frail and elderly, he thought he could still swim with us at the beach, but couldn't. He got caught in the riptide and sucked under. I had to pull him from the water, with my toddler son tucked under my left arm, wearing his rubber ring, and my right arm under my dad's arms, to haul him out. My mum was at the water's edge, taking a photo, oblivious to the danger we'd been in.