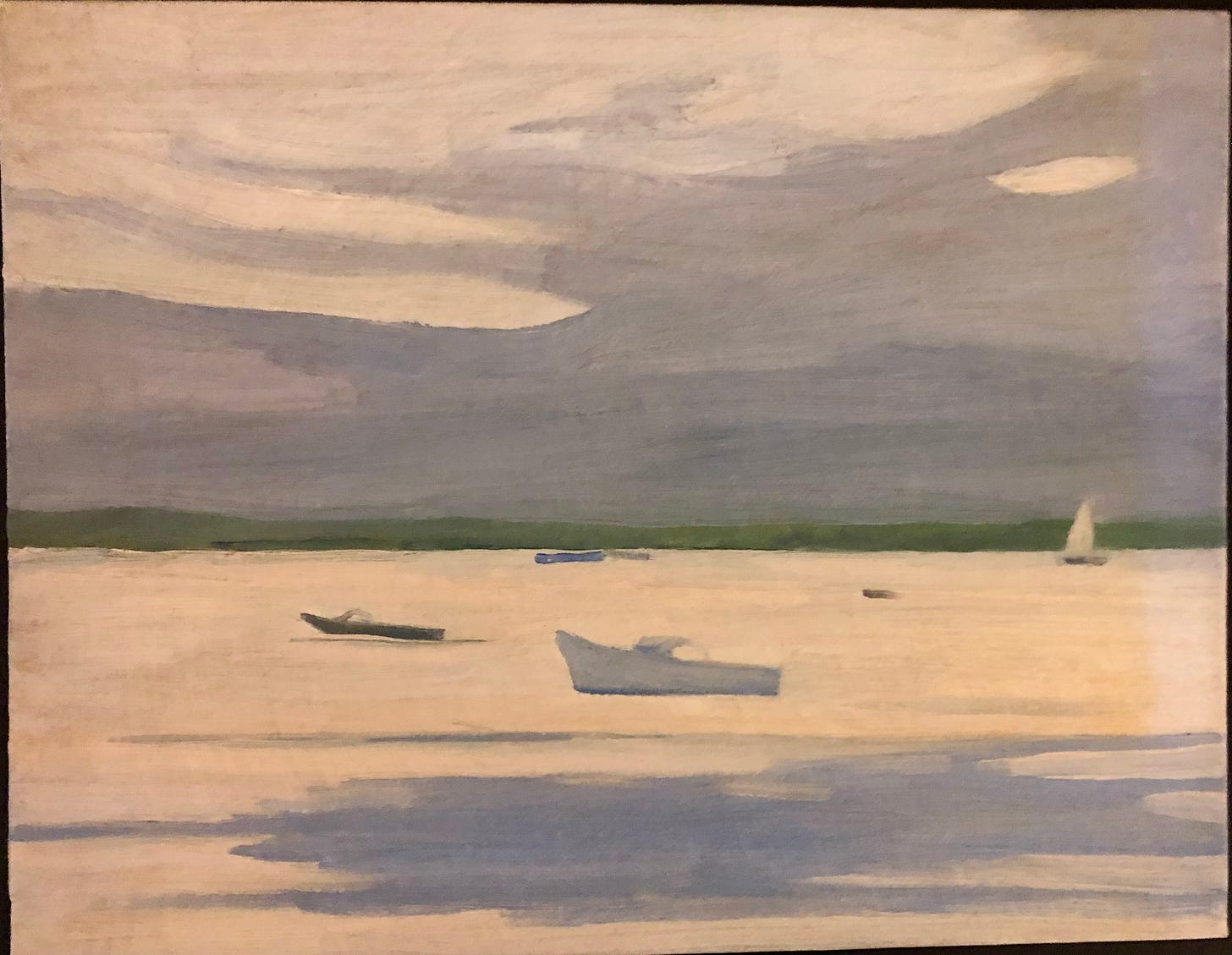

Two Houses. Two Painters. Two Parents. is a newsletter of stories about art, feminism, grief, and time excavated from the Soho loft where I grew up. Posts are free and illustrated with the work of my long-divorced parents, the painters Mimi Weisbord and Lennart Anderson.

Last week, while writing “Hoarding Vindicated,” I was on a mad mission to find certain images to illustrate my post. I dug in tubs at the top of our barn, the Tupperware in my office, and the storage unit I’ve rented since exiting my mother’s overstuffed loft. I know I have photos of art historian Eugene A. Carroll with his convertible in Western Mass and with my parents dressed for a cocktail party in Rome. But I never found them. Then, following my posting, my brother sent me this low-resolution image from his Facebook page in 2016 (posted on the occasion of Eugene’s death).

Nevertheless, digging and sorting had unexpected payoffs. I found three more letters from the painter Marcia Marcus. Though unsigned, I found them because I’ve learned to recognize her handwriting and because I now know her married name was Barrell. My experience identifying these letters and envelopes among piles I’d already examined reminds me not to throw anything away. As my father might say about painting from observation, I’m learning to see.

It was satisfying to email the find to Marcia’s daughters. Again, I had the pleasure of surprising them with Marcia’s voice from 60 years ago. This may be the most important dividend to my mother’s (and my) hoarding: providing others with meaningful time travel, filling in gaps of knowledge, or illuminating and breathing life into what is known. Letters contain myriad small things, turns of phrase, references, and hints of character that may only be observable by their authors’ children and others who knew them intimately over a long breadth of time.

(I feel similarly about my parents’ paintings.)

Of course, not everyone has this kind of relationship or sustained interest in their parents. I attribute my heightened attention to certain factors: their vying for my loyalty, the need to track their rules and keep my boat floating between them, the visual feast of their lives, their infectious habits of observation, theirs, and my (very different) quest for light and air.

In my parents’ letters, I recognize traits of character brightened by youth and see how long they were them. I also hear a rushing current of hopefulness that I experienced reduced to a trickle. I don’t think that’s true just of Mimi and Lennart and their bitter divorce; it’s the arc of a lucky life. In Lennart’s letters, I recognize his way of observing, his doubts and anxieties, and my mother’s in hers, but they were also on the move, eager for each new chapter, everything just unfolding.

Our parents and children offer steady vantage points on human development—of a time and place—but if I squint like my father did, holding his brushes, the perch is also for all time.

I love your attention to process— the finding and sifting and sharing and interpreting of parental artifacts. Yet you have a light touch too. One’s parents are always sort of a mystery, or maybe even unknowable.

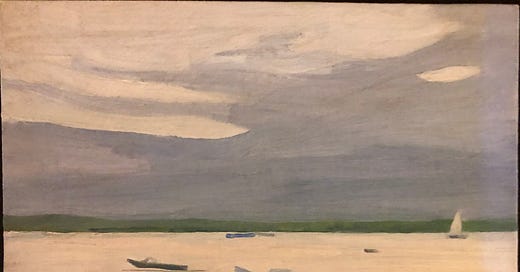

'Theirs (and my very different) quest for light and air' - followed by that airy lift of the darkest-toned boat speeding left in that reflection of sky and water in subtle corals and chromatic greys - how well your words work with that beautiful picture!