On Myth Making, the Muse, and My Father (the Painter Lennart Anderson)

How do internal conflicts get you creating?

Two Houses. Two Painters. Two Parents is a newsletter of stories about art, feminism, grief, and Time excavated from the Soho loft where I grew up. Posts are free and illustrated with the work of my long-divorced parents, the painters Mimi Weisbord and Lennart Anderson.

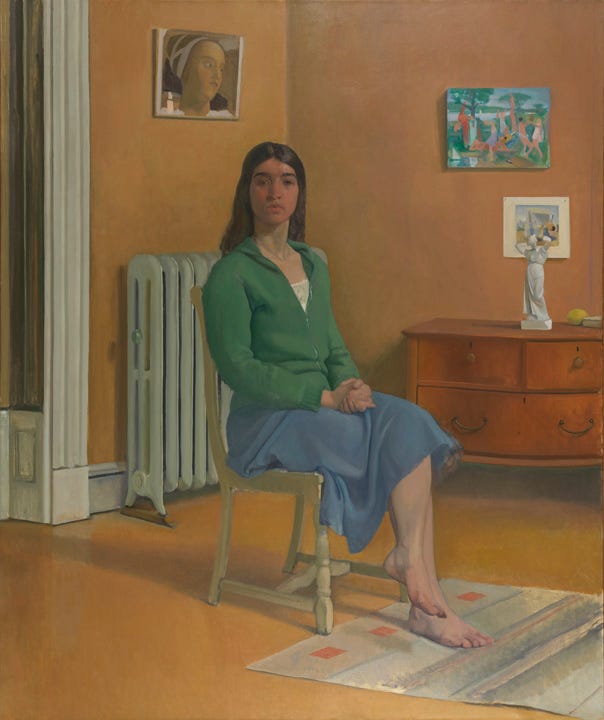

Portrait of Barbara S. conveys a quiet dignity. She was then my father’s girlfriend; the picture was painted about 1976, ten years before they married. I remember the painting in his studio. I remember teasing him with something like, “Hey! She’s got clothes on this time.” The remark cut to a certain heart of things. (I see him shifting his weight, brushes in hand.) Often, I blurted what was supposed to be left unspoken.

Portrait of Barbara S is in the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. It’s not included in the Lennart Anderson retrospective that is currently on view in Chicago. Still, other portraits of her are there, as well as my father’s reimagining of the myth of Jupiter’s “seduction” of Antiope and Idyll III, which feature Barbara’s youthful form.

It’s reductive, but the portraits are, for me, a kind of respectful foil to the nudes. I suspect they were for his wives, too. At a certain point, Barbara stopped posing nude (though she’d continue to show up as a figure in his large Idylls begun in the 70s). She was eager to move from her position as muse and model to wife and mother.

Portrait of Barbara S holds a tenderness, stillness, and, significantly, a steady gaze from subject to painter. There’s also a childlike quality underscored by her ruddy bare feet that was in keeping with her person.

When I quipped about her wearing clothes, he didn’t laugh or shrug it off as I expected (which is why I probably remember it). I came away with the sense that he owed her this large, elegant picture.

Barbara returned as a nude to his canvas with Jupiter and Antiope in 2004, painted after her untimely death from cancer. Though Antiope avoids being specifically Barbara, the figure is hers (he acknowledged). This is an astonishing choice to make for reasons obvious to any viewer.

But more so for me.

In October, I published My Strange Inheritance - Lennart Anderson’s Jupiter and Antiope, an essay that plays off this painting’s reception at the Steven Harvey Fine Arts (SHFA) website. SHFA held an exhibit of this masterwork and its studies last fall.

In my father’s reimagining of the myth, SHFA finds “a dynamic tension that invokes the relationship between painter and model with Jupiter as stand-in for the artist and Antiope as his subject.” The painting references “the history of the figure model and female nude in European painting.”1

Seen this way, Jupiter and Antiope is confessional. The artist conflates the myth of the rape of Antiope, with the gaze of the painter on his muse. The myth’s story, after all, is procreative. Antiope is impregnated with twins, her body, her person, appropriated by Jupiter.

(Lennart admired Titian.)

In this way, he acknowledges a harvesting of his relationships for his art, relationships that were made more difficult, he was aware, for being bound by his narrow priorities. He had staked his life’s purpose, and family came second, a problem he confessed to me, seeking my understanding (and sympathy for Barbara, the stepmother who treated me cruelly).

Jupiter and Antiope hung in the stairwell of his house in Brooklyn, just outside his studio door. I both avoided and was transfixed by its conflicted layers of emotional energy: menacing, saturated with grief and guilt, yet - hauntingly - born from his being free of her (their relationship always so turbulent). I was made uneasy by the painting’s palpable restrained (abuse of?) power. It grieves her passing. It pays her a certain homage. But she would have hated this picture. He made a painting that would not have been possible had she lived.

And he knew it.

“The tableau works on my father’s canvas,” I wrote, “where his muse is forever unconscious. Where Jupiter broods, aware of his power. Where Antiope is a Nude for all time, beautiful, vulnerable, captured sublime.”

My father saw the world in art historical terms.

It was his stubborn lens. Also, his blind spot.

When I was ten, he pressured me to pose for him with just a towel to my chest. I turned him down, miserable with how he’d keep returning to it. He’d apologize but then grow more insistent, often in passing, as if he couldn’t help it. It was distressing and, for a couple of weeks, a miserable secret drama between us. I did not carry this agony to my mother in Manhattan (as my brother did under similar pressure). I knew she’d be enraged, and I knew to protect my father.

Anderson has said that he paints ‘how things fall together and separate out.’

- the SHFA website

Instead, I kept the peace, the scales of their separation invisibly balanced on my neck.

(Lennart was a great admirer of Degas.)

Eventually, he painted the girl without me. Later, he transformed that figure into a boy (standing with a stick in the foreground).

Idyll III was painted over decades, and the episode with me was short-lived. But I can say I know the gaze of Jupiter. It was a different kind of lust, and its surfacing abducted my father. He was a warm, funny, loving man, anyone will tell you. But for his painting, he’d grow horns like a Satyr.

There’s a price to pay for this kind of dedication. I pay it myself when I am preoccupied with writing. My family pays, and we don’t much romanticize it.

It’s painful, the way things come together and separate out.

He spoke to me as if I understood that his gift was his calling and his problem — self-conscious, embarrassed, seeking compliance with a need that swept across boundaries like an invading army.

It’s not always easy for me to enjoy panel discussions or articles about my father’s work. Often, they feel like myth-makers, affection for him spilling into territory outside the planes of the picture. I understand it. I adored him, too.

But I had two painters for parents, and my position caught between them was so fraught, I’ve needed to get to the bottom of matters more than I’ve needed to stay tethered to my affections. Since their deaths — since inheriting the time capsule that was my mother’s loft — I’ve felt free to ask, Who were these painters who raised me torn between them?

This is the psychic work accompanying my excavation of their artwork (and letters, photos, and my mother’s journals). As his daughter, I might have the least objectivity in contributing to understanding the work of Lennart Anderson.

But that may not be true.

Portrait of Barbara S. (the first one) was painted in 1972, the year my mother left him for the Women’s Movement. He’d met Barbara as a student in his classroom at Richmond College. They dated, but a year later, he was trying to get my mother, Mimi, back. His studio work had stalled. He’d taken an advance from Graham Galleries to focus on his art just as his family was falling apart.

My mother was disgusted.

She left with our beds for her new apartment; my father slept me and my brother in his studio, his large street scene, St. Mark’s Place, the backdrop to our nights there.

Painted over years, the woman on the stoop once held a knife in her hand.

Critics have noted that portraits of Barbara are imbued with intimacy. Indeed, painting and communing with oils may have been his most intimate act. He transformed his relationships on the picture plane, a two-dimensional surface he could control. Painting was a kind of offering. Sometimes, an apology. Sometimes, something else.

Panels on my father’s work make me restless and frustrated and restless with feeling restless and frustrated and then inadequate to the task of being his daughter, which initially had to do with having never studied art (outside of osmosis) and not knowing the difference between tone and value. But that is not the real problem; the problem is this feeling that I know the things that don’t matter, yet are a kind of everything: his worn corduroys, the size and feel of his hands, his enduring contradictions, how his life’s calling was also obliterating.

As I grew up, and afterward, people would occasionally speak to me with a tone of gentle admonishment, a need to impart, to check me, to make sure I understood his place and mastery, and their reverence for him, which should also be mine, they implied, though they did not know the corduroys, hands, and enduring contradictions as I did.

This may be the final stop of the Lennart Anderson retrospective. I don’t know. Stewarding his legacy is not my project. My half-sister Jeanette, born to just one artist, has devotedly taken this on. What I do know is this occasion thrums in my person with a grief that’s been long held for him, me, and all the splintered shards of my family. My mother’s loft and what it contained — buried memories, art, letters, artifacts, her paintings, and some of his — are his retrospective’s invisible extension.

After his death, the Lennart Anderson myth-making was unexpected. I was unprepared. But now I’m grateful. It exerts a pressure that transforms my inner dialogues to words on the page, a lifetime's yearning made possible. (Write! My mother had practically demanded, discouraged to see my passions untended.)

Of course, my father would have wanted his myths left alone. He contributed amply to his myth-making. But I know enough as a writer, observer, and excavator to see how internal conflict can drive the best work, that wrestling. Something that needs working out. It either dooms or makes the piece. And so this history is relevant. He channeled tender compassion for Barbara in these pictures. Aware of his power. Also, something else — I still can’t resolve it — his calling outside of all of us.

In an Artist's Studio

One face looks out from all his canvases,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens,

A saint, an angel — every canvas means

The same one meaning, neither more nor less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

Related posts:

Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects. (n.d.). Jupiter and Antiope | steven harvey fine art projects. Retrieved September 15, 2024, from https://shfap.com/events/jupiter-and-antiope/

Hannah Gemeny’s Mutual Art article, “From the Perspective of the Model: Elizabeth Siddal and Christina Rossetti,” arrived in my inbox as I was writing this post. Rossetti’s poem is in the public domain.

I’m reading you for the first time and consider this essay a great gift. Your gift of a beautifully told struggle as well as pathways to memories and challenges of my own.

Thank you. I’m your reader now.

Eliza,

This is such a rich exploration of the tension between artist and subject. I really enjoyed reading this. thank you for sharing.