Two Houses. Two Painters. Two Parents. is a newsletter of stories about art, feminism, grief, and time excavated from the Soho loft where I grew up. Posts are free and illustrated with the work of my long-divorced parents, the painters Mimi Weisbord and Lennart Anderson.

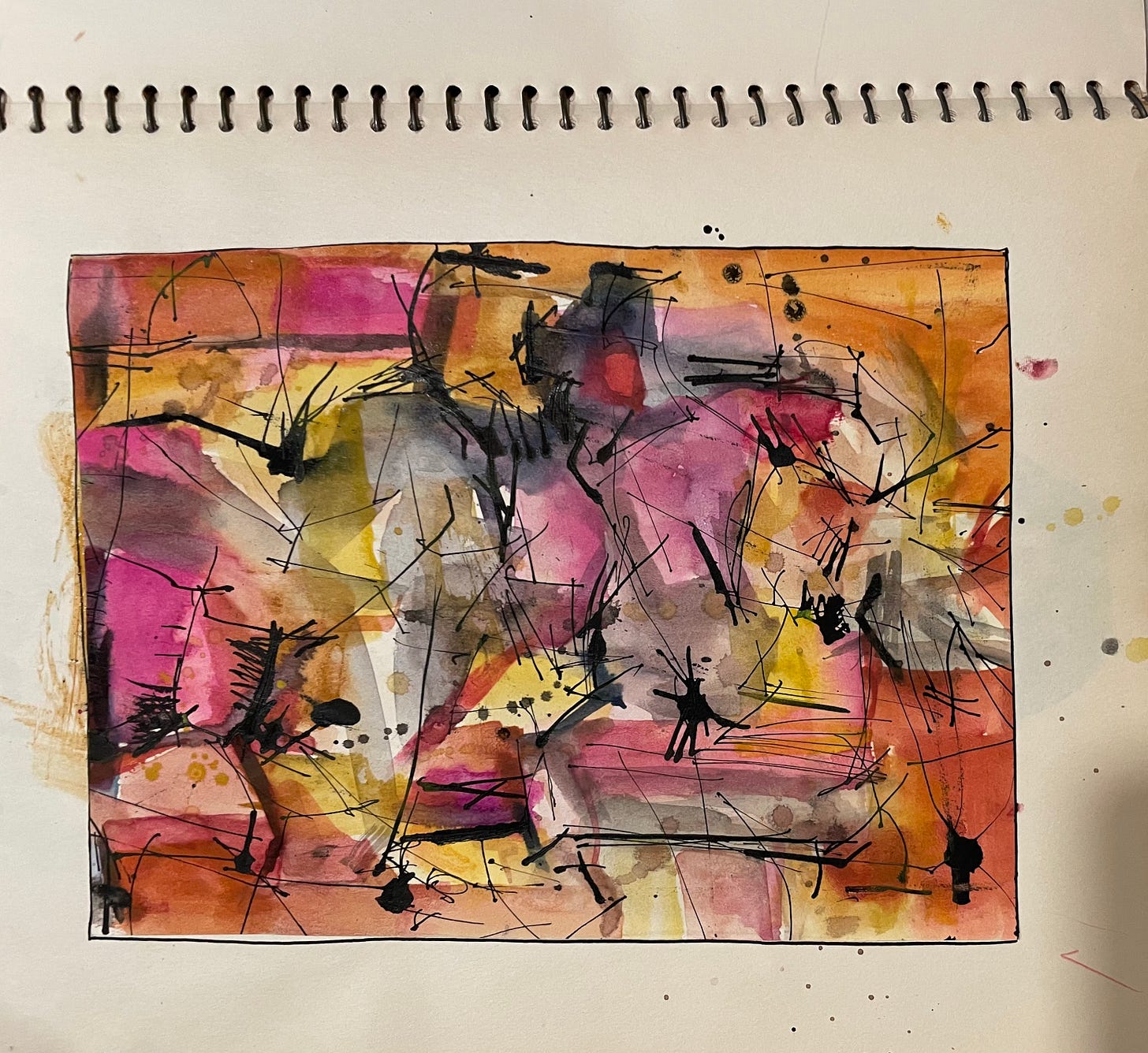

I found a little abstract expressionist painting in my mother’s sketchbook from when she was 21 years old.

I’m sorry for the shadow on the right. I gave this sketchbook to my cousin, and these are photos I took hastily with my phone during a recent visit to him.

This page is the only abstract expressionist work I’ve seen of hers. While considering this post, I realized it was painted the summer Jackson Pollock died in a drunken car wreck in East Hampton. With its ink splatters and lines on watercolor, I can’t help but wonder if she didn’t make it in response to learning of his death. She was in Manhattan that summer. She had a commercial art internship and was living with other college students from the University of Illinois.

Pollock was a founder of “action painting,” a kind of abstract expressionism that today every art camp is teaching ten-year-olds. In the 1950s, Pollock’s splattering gestural approach was part of what became known as the “New York School of Abstract Expressionism,” the movement that distinguished painting in America at mid-century. Painting for paint’s sake, referential of nothing but the self (art critic Clement Greenberg argued in essays, championing the movement).

Except by the late 1950s, the paintings were often seen as derivative of each other (art critic John Canaday insulted many in the New York Times). Painters and painter wannabes were moving to the city in droves to join the New York School. Abstract expressionists from this era are today referred to as “first generation” or “second generation.” You are either a founder, or you hopped on the bandwagon (though that’s a derogatory, gross oversimplification).

Besides Pollock, my mother’s little watercolor brings to mind Helen Frankenthaler's cloudy, soaked technique with its fluid shapes. Knowing my mother, all of these influences are possible. She kept up with the times.

In the 50s, the pressure to abandon figurative art was so great that in ‘59, the painter Marcia Marcus wrote my father (the painter Lennart Anderson), “Have you turned abstract yet?”1 He did try a couple of little ones but didn’t keep them. I’m glad to have my mother’s.

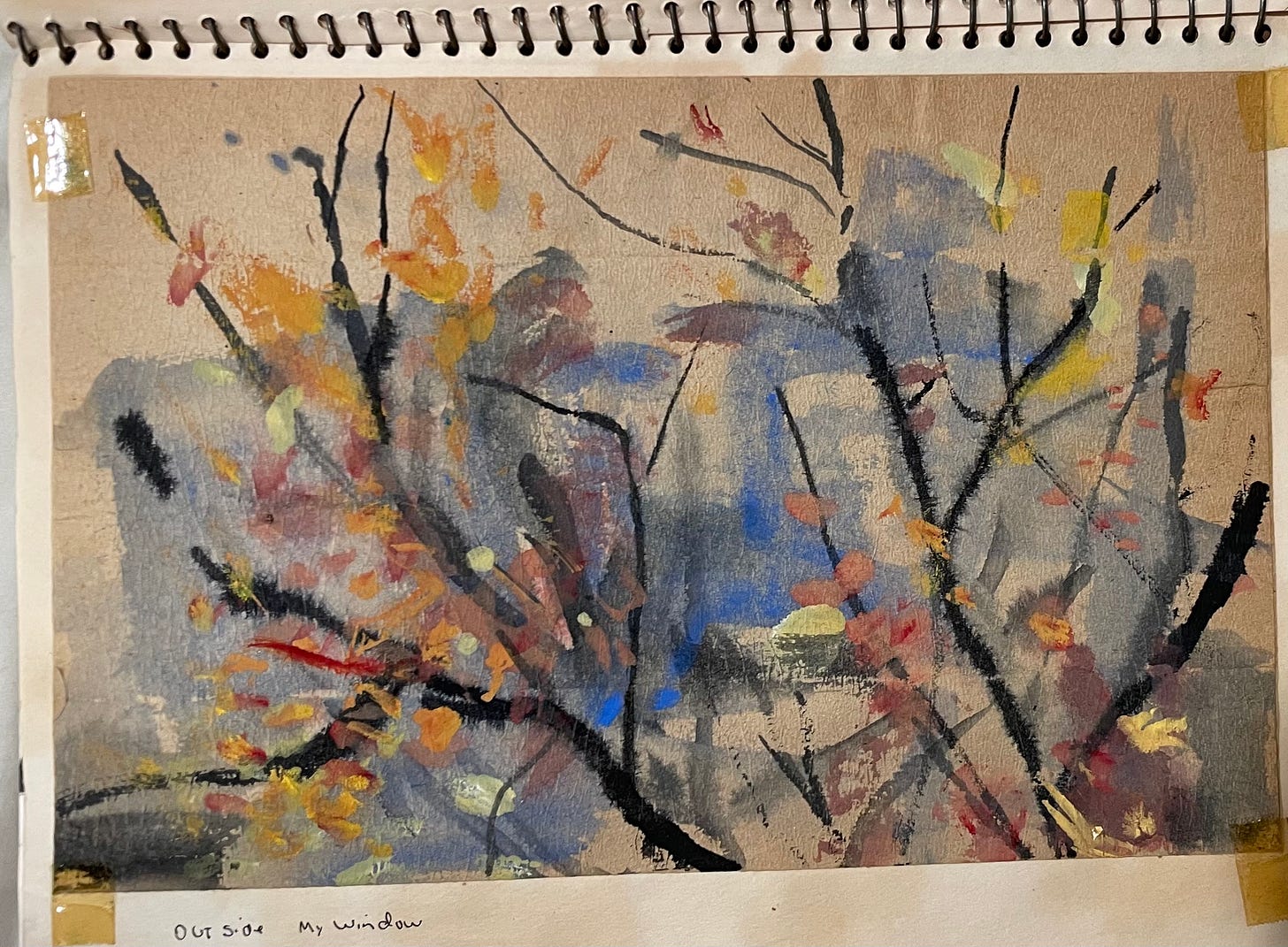

In her sketchbook, Mimi immediately returns to elements of figuration. For a moment, I thought I’d found another purely abstract piece, but then I discerned her tree branches.

The page is captioned “Outside my window.” She was living on leafy Riverside Drive.

Abstract expressionism would not have been possible without a turn away from representation earlier in the century. In his introduction to Cubism and Abstract Art, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. —the founding director of MoMA—wrote in 1936,

“The pictorial conquest of the external visual world had been completed and refined many times and in different ways during the previous half millennium. The more adventurous and original artists had grown bored with painting facts.”2

I read this quote in “Art and Authority,” critic Carter Ratcliff’s latest post on Substack. Ratcliff refutes Barr’s declaration about the “conquest of the visual world.” He asserts,

“Representing the world’s appearances is not a project that can ever be completed. To transpose the look of things to canvas is a speculative process relaunched every time a figurative painter picks up a brush—or a new painter chooses figuration over abstraction.”

Ratcliff’s words inspired me to share my mother’s sketchbook. They also reminded me of a moment with my father in the mid-80s.

A high school friend was supplementing her schoolwork with art classes somewhere in the city. Boasting in our living room, she told Lennart she was studying painting that fall because she’d already learned to draw.

“Really?,” he replied. “Good for you. As for me, I’m still learning.”

In her sketchbook, my mother is trying different approaches. She’s staying loose and not self-editing, as she will for decades to come. She’ll even abandon figurative art for a while in the 80s. But in her sketchbook, though she is yearning for New York’s art scene, she is — as Ratcliff respects— “a new painter choosing figuration over abstraction.”

Many of my readers know more about art than I do. I’d love to hear from you if you have something to add or correct or something you notice or see. Regardless, I love comments here and appreciate your “likes.”

Barr, Jr., Alfred H. Cubism and Abstract Art. New York. Museum of Modern Art, 1936, p 11.

I love that you're keeping your mother's legacy alive by sharing these beautiful works in her sketchbook. My mother was also an artist, and I only unearthed her sketchbooks when going through her effects after she passed in 1918 - at almost 101. I learned a lot about Mom's muses and influences by flipping through.

We organized a retrospective for her for a benefit for the Art Academy of Cincinnati, where she was their oldest known alumna, having studied there in some capacity from her high school years in the 1930s through the 1960s. The art curator at CAA gave the most remarkable tribute by comparing elements of her work to the influences of her teachers, among Cincinnati's finest. I only wish Mom had been there to enjoy the posthumous celebration. (But then again, maybe she was!)

In case you're interested, ere's a blog I wrote about Mom's artistic career--and limitations--in the lead up to her retrospective https://www.artacademy.edu/news/dottie-stevens-100-years-impressions/

Fascinating how edgy this sort of expression must have been at the time.