Two Houses is a newsletter of stories about art, feminism, grief, and Time excavated from the Soho loft where I grew up. Posts are free and illustrated with the work of my long-divorced parents, the painters Mimi Weisbord and Lennart Anderson.

Recent discoveries have me considering my mother, Mimi Weisbord, as a historical person. They put my troubles with her in a jar, as inevitable, as something I could never have repaired. There’s peace in learning this. It may be the end of a long subconscious quest.

In an earlier post, I wrote about Mimi’s journey back to oil painting in the 1970s after she left my father, the painter Lennart Anderson. Now I understand that in 1958, the year they married, she was on her way to becoming a master printmaker at the dawn of a great printmaking era. Instead, she married Lennart and boarded a steamship to Europe for his Rome Prize. I did not understand this while she lived or even while excavating her loft after she died. But findings over the last several weeks suggest she had this secret that was, for a long time, in plain sight, and eventually, she swallowed it and carried it around inside of her.

Mimi did not talk much about her life in the 50s (outside of a shudder for being a woman in that era), and never about the period in New York City with my father before they married. Now, I think this is one reason why: the promise and abandonment of this early work and moment as her own artist. I suspect it had a corrosive effect on her life, like an etching’s copper plate invisibly burning its acid mark behind the decades I had with her.

(From my life with my mother: “Mom, would you like to paint motifs on the walls of your first grandbaby’s room?” Mimi: “That’s not the direction I want to take my work right now.”)

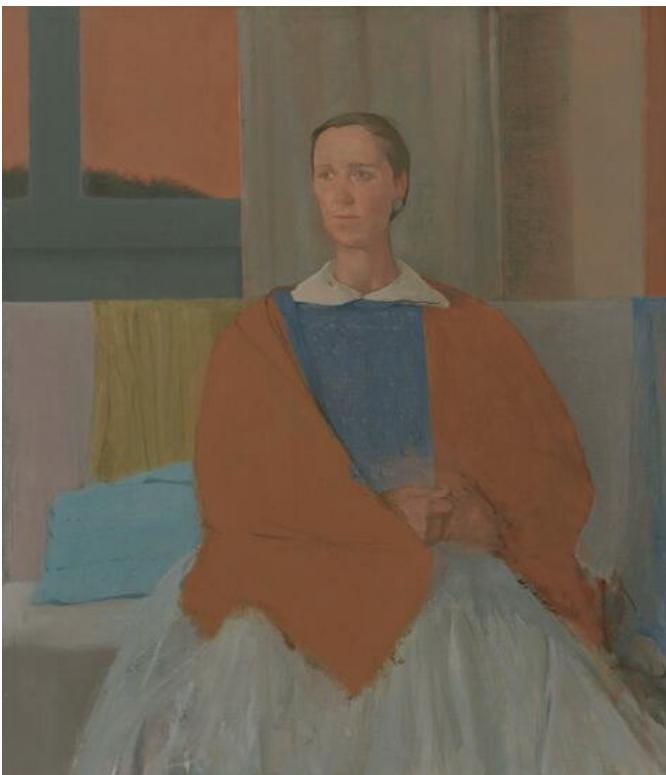

This regret seems crazy to suggest because those three years living at the American Academy in Rome were the most formative of their painting lives. Living with other prize winners and fellows, they were wined and dined, and they painted and traveled. How could she regret them? Their time in Rome was a continuous reference point as I was growing up: the pasta on our plates, the art on the walls, Italian expressions (Lennart’s “Andiamo!” to get us out the door), Mimi’s Ferne Branca and her chicken marsala (that I will forever miss), his large Idylls (he called “wall art”), her Pompeiian mural commissioned by CityArts. In Rome, his palette changed, warming with oranges and pinks (reflecting the Academy’s walls), as did hers—I now understand—when she turned to oil painting upon arrival.

IN 2019, Mimi moved into a memory care residence on Long Island, and I discovered a bundle of letters in the loft that she’d written home from Rome (initially preserved by my grandparents). They are jubilant, rich with detail, and sometimes include little illustrations. (“The floor of our bedroom and studio is red tile, and we use napkin rings and hammered brass finger bowls.”) They reference how they spent their time, what they were working on, who they met, how they ate, local customs, and time spent with their Italian best friends who had a place outside of Florence with a frescoed bedroom.

I consumed these letters in a few eager gulps and considered their content with latter-day events and moments of being: Lennart’s eventual fresco-like Idyll he painted on the wall of the bedroom she’d left behind, my mother’s stunning comment when she saw it, returning to the house for his wake after more than 40 years: “We’d always talked about doing that in there.”

The letters made me realize that just months before boarding that steamship to Europe, she’d had a large intaglio reproduced in The New York Times. Growing up, I knew about her print in the paper, but I did not know it was published during the period they were deciding to marry.

Woman in Black is a brooding self-portrait that hung on the wall of my grandparents’ and my aunt and uncle’s. Its subject seems closer to age 50 than her 22 years, and it disturbed me.

A clipping I’d seen in a scrapbook showed Woman in Black reproduced in a Sunday edition of the New York Times (NYT) with prints by two other artists. Each was selected from the Brooklyn Museum’s National Print Exhibition, a biennial that took place during the time of her fellowship at the museum’s art school.

Mostly, what I knew about that reproduction was the NYT had misspelled her name as “Weisbrod.” (“Wise broad,” I teased her, learning this as a child.)

The error was the sort of thing that would happen to her, she seemed to suggest in the telling of it, as though recognition for her was so elusive that when it came, it didn't fully arrive.

This was the reason, I presumed, that her print’s success was a source of pain rather than a source of pleasure. The truth is more complicated, I see now; but growing up, that print was also old news, not something discussed, and I never absorbed the year it was published, only that it was before I was born. Just as I didn’t think about what year my parents had married because by the time I might have had any interest — or awareness that every divorce is preceded by a wedding — they were arguing the terms of their split and our maintenance, an argument that consumed my childhood and shut down most inquiry into the past.

Only once I started digging in her loft did I begin connecting the dots: 1958 was a pivotal year for both of my parents.

IN 1958, Lennart and Mimi were on E. 4th Street, where they slept on a cot by his paints. Mimi was completing a Max Beckmann fellowship at the Brooklyn Museum Art School when Lennart turned down a Fulbright to accept the Rome Prize. That April, her intaglio print was in the paper. By August, they married and took a honeymoon in Provincetown (the beach haunt of the NYC art world). Then, in September, they crossed the Atlantic and spent weeks in London and Paris before arriving in Italy.

I was dazzled by how high they’d flown before their spiral crash landing.

I was so surprised that in 2019, I stood at the foot of Mimi’s bed in her assisted living residence seeking confirmation of the order of these events, afraid of getting in trouble for going through her things and finding her letters, but she was ill and losing her mind.

It was now or never.

“Mom, did your self-portrait get into The New York Times just a few months before you and Dad boarded the steamboat to Europe?”

She regarded me with those large dark eyes, the exact brooding look of that self-portrait.

“Yes,” she finally spoke. And with a wisp of exasperation, “That’s right,” she added, still holding my gaze.

I felt something lock into place between us then.

A MONTH ago, I found that NYT edition online and saw why the clipping I’d seen excluded text; there doesn’t appear to be an accompanying story.

Her print’s prominent position on the page, however, astounded me.

For context, I began reading the adjacent article about the fire at MoMA (“Crisis Averted”) and found that the piece transitions to bemoaning the United States Information Agency’s plan to broadcast American art via embassies. The Agency planned to distribute print reproductions of paintings: a ridiculous thing to do to a Jackson Pollock, art critic Howard Devree writes; much better to hang original works of accomplished up-and-coming American printmakers such as are on exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum’s National Print Exhibition.

“Out of more than 1200 works submitted, the jury accepted 136 from 27 states, showing that the print revival since the war is still vital and growing," records Devree.1

I had no idea the exhibition was so competitive. I’d assumed she was in it because she was studying at the museum’s art school.

I called my aunt. We discussed Mimi’s moment of fame, and she recalled just staring and staring at Mimi’s intaglio reproduced in … Time Magazine.

Time Magazine? I vaguely recalled people saying they thought her print was in Time, too. But my mother had never mentioned it.

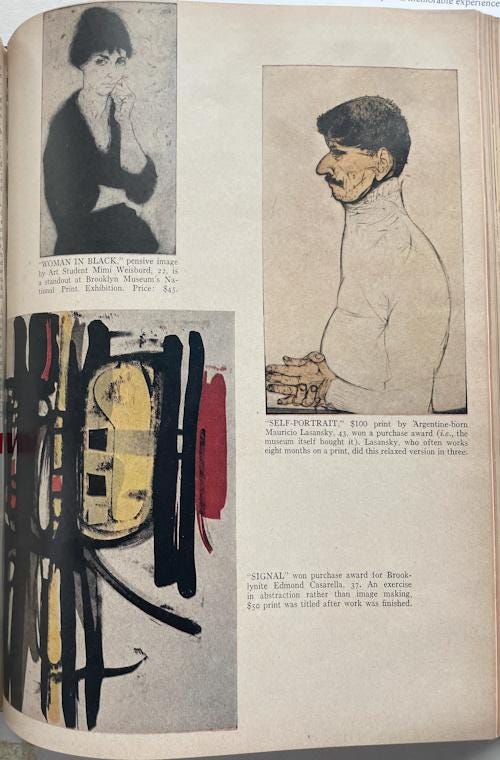

On eBay, I found a bound volume of the 1958 Spring Time editions. Keeping the faith, I flipped through many weeks. Woman in Black wasn’t published in April as it had been in the newspaper. Or May. In Time, I found her in June, and again with prints by two more artists.

But only Mimi Weisbord is in both publications.

More surprising was this: Time published Woman in Black above an abstract by Edmond Casarella, who was then teaching at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, and alongside a self-portrait by the artist considered “the father of modern printmaking,” Mauricio Lasansky.

Lasansky, highlighted in the adjacent article as “Perhaps the most influential print-man in the U.S.” and “the driving force behind the University of Iowa’s thriving print department [...],” is quoted on the growing importance of prints in the U.S.: “‘The most promising printmakers are young men under 35,’ he says. ‘If they continue at it, they will be masters at 45 or 50.’”2

Mimi was just 22.

Digging further, I found a Brooklyn Museum webpage about the exhibit (with photos of the show hung in the second-floor gallery) and a press release that explains the exhibit will travel throughout the U.S. via the American Federation of Arts. A catalog had been produced, and the press release names Mimi Weisbord among the exhibit’s highlights “as one of two young artists who contributed sensitive portraits in black and white.”3

Growing up, I remember when my father had a painting in Newsweek.4 I remember an incredible sense of pride; he’d made it into a popular mainstream publication. It’s astonishing to learn my mother did the same thing but decades earlier. And she did it as an art student at a time when “The most promising printmakers are young men under 35.” It’s an inversion of the logic I grew up with. It’s like realizing Ginger Rogers was dancing backward in heels the whole time.

Arriving at the American Academy, Mimi writes home as though they’ve both won the Rome Prize:

Today Mr. Roberts [the Academy’s director] called a meeting to make sure we understood we are under no pressure of any kind. They don't care about quantity of work and expect us to spend the first year getting adjusted, traveling and looking around. […] They also make the beds, clean the studios and change your money for you. In other words, they want you to be completely free to concentrate on your work.

But then Mimi discovers she does not have access to the American Academy’s print studio. “I will start print-making as soon as Wanda Matthews gets back from Iowa, where she had to go for a while.”

Matthews is in Rome on a Tiffany grant and has taken over the print equipment. She’d finished her MFA in Iowa the year before as a graduate assistant in Lasansky’s print department.

Mimi immediately pivots to painting, “I am working on a large still life that I think is the best I’ve done. It’s on the order of the large yellow flowers that’s in the basement. But with fruit and things in it.”

(I’ve found those yellow flowers, and I’m confident this still life is the marigolds above.)

My mother was a talented painter, but I see the challenge of returning to painting as the wife of Rome Prize Fellow Lennart Anderson. I also see the freedom printmaking had offered her, a medium he never touched. In her letters, however, there is no suggestion she ever gains access to the Academy’s print studio.

Regardless, Mimi soon had nothing to print or paint toward. During the second and third years of Lennart’s fellowship, wives were excluded from showing their work at the Academy exhibitions. “I went to Rome an artist and came back a wife,” my mother journals decades later.

BY THE early 70s, the women’s movement awakens Mimi to her losses, and she becomes enraged.

Now I see that she was also angry at herself.

She’d once told her second cousin (the artist Dotty Attie): “I used to be ambitious, but Lennart’s doing everything I wanted to do, and that’s enough for me.”

She’d bought into those 50s-girl lies.

In her memory care residence, she spoke mostly in dementia’s metaphors and conspiracies. She could, however, return to the past with ease. I was thrilled when she recalled the fruit on the train to Rome, the size of the grapes. (She’d drawn them in a letter.) I was thrilled we had something to talk about other than her violent rants and allegations. I asked her about Greece, where she and Lennart had first painted en plein air. In one letter, I’d found a beautiful little photograph she’d taken of Lennart with his paint box by a Greek cove.

“I scouted all the best places for him,” she smiled and then finished with a laugh, “I was such a stupid asshole.”

In her journal from 1980, she ponders her decision to marry my father.

Suppose I hadn't married L. but let him go to Rome while I stayed on in New York [...] I could have hung out downtown with the people I already met and showed a painting or two at the March Gallery. Gone to shows & the artists' club […] It would have been great if I could have gotten a part-time job to support myself with—and taken myself seriously as a responsible person and an artist. Worked in spite of people’s or the culture’s preconceived ideas about my life.

She is writing during one of the toughest periods of my childhood. We’d recently settled in Soho; it was before she started teaching at City College; she was heartsick and struggling to afford her life as an artist. She doesn’t reference print-making at all; she doesn’t touch this history. About going to Rome, however, she does write: “We never discussed my success as an artist.”

When I read that, I had to think for a moment what success she meant. I didn’t know all of this history.

I didn’t know she was haunted by Woman in Black.

IN MY next post, I’ll connect these revelations with the women painters in Lennart’s world of the 1950s.

If you’re reading and you have something to add, I hope you’ll leave a comment here on Substack. Perhaps you know something from this time, or you’ve had similar experiences with your own parents after their deaths. I find I’m often learning and pivoting. There’s an important pivot in my thinking coming. My uncle told me that my mother once said she regretted giving so much of her time to the women’s movement. I didn’t believe it, but I’ve rubbed that stone in my pocket for several years now, and I see something new there.

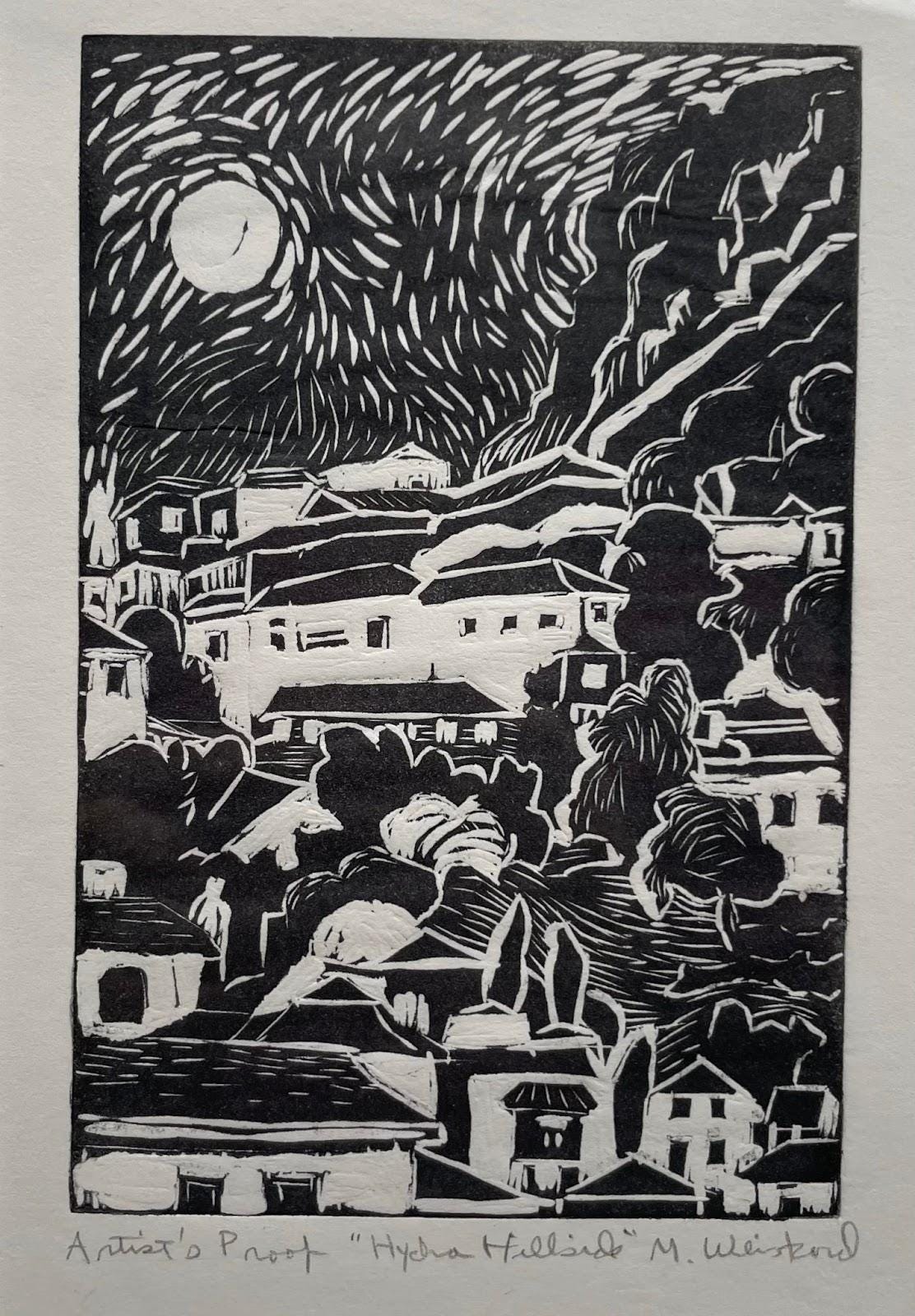

I’ll end with a little linocut she made (in this century) of a hillside on the Greek island of Hydra. Now I see how she returned to reclaim those places, the projects she took on, and the satisfaction they gave her.

Now, when I lock eyes with Woman in Black, I am still haunted. But I believe I understand her.

Devree, Howard. “Crisis Averted,” New York Times, April 20, 1958, Section X, Page 11.

“Paperbacks of Painting,” Time, June 2, I958. pp 62-63.

Brooklyn Museum Archives. Records of the Department of Public Information. Press releases, 1953 - 1970. 1958, 028-29.

Stevens, Mark. “Art Imitates Life: The Revival of Realism,” Newsweek. June 7, 1982. p 65.

Gorgeous piece! I am so fascinated by this process of reevaluating childhood assumptions and memories and discovering new truths. Can’t wait to hear more….

Fascinating! Many, many echoes with my mother's story as an actress married to actors in the 50s/60s/70s.

On another note, I love how the warm Italian orange made its way into both Lennart's and Mimi's work.