“Only you hold the cathedral of your story.”1

What if postcards in racks winked with people from our past, like iPhone memories? My mother kept a collection of photos in a firebox, and some were blank postcards. Digging through, I’ve pushed those aside.

Until now.

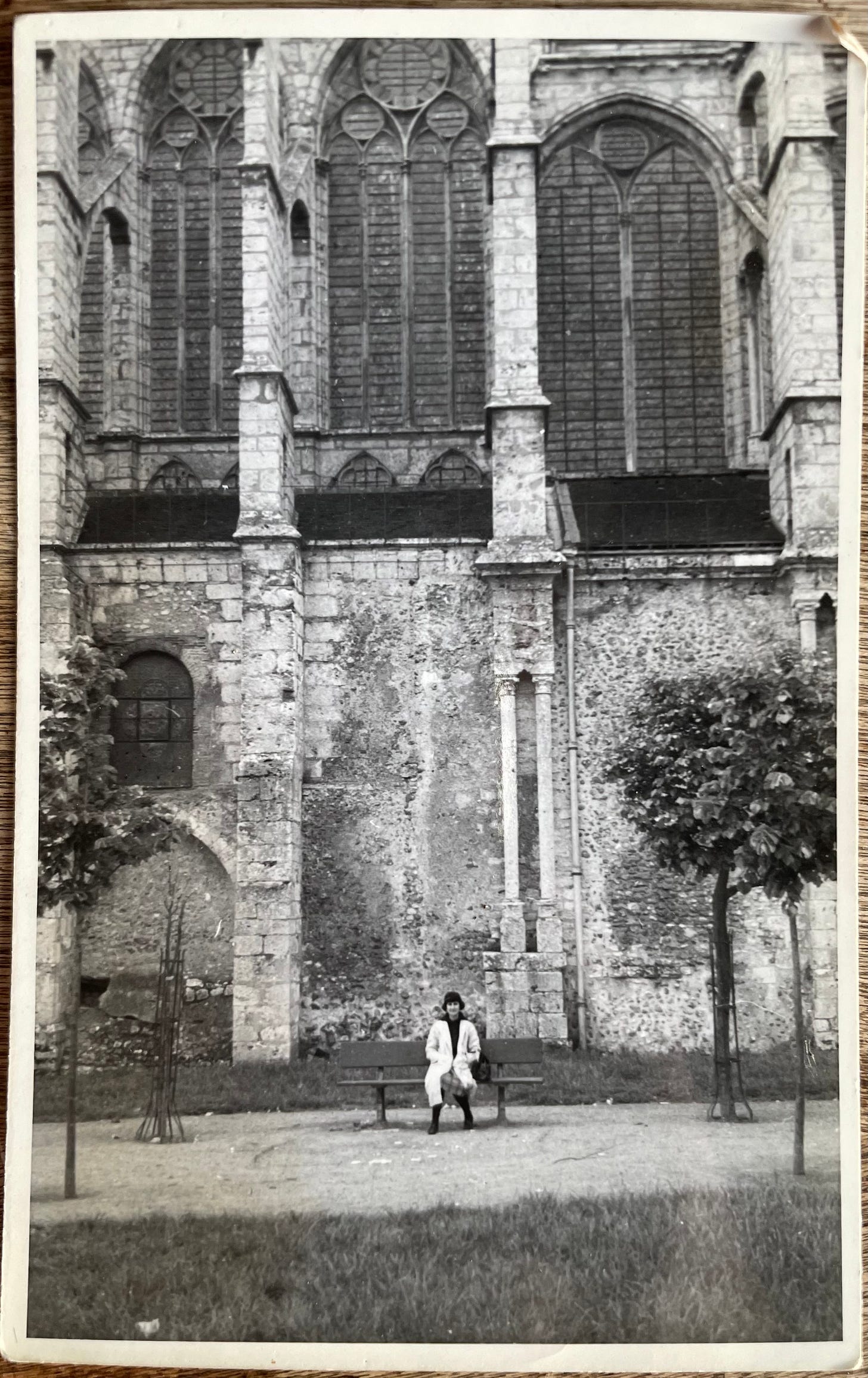

This morning, I flipped one over to find the image of a woman seated, tiny before a cathedral’s wall, and on second glance, looking so much like my mother that I magnified her using my phone’s camera.

There she was, smiling, young and healthy, waiting to be recognized—sending a shiver through me.

In “Left Behind,” Mary Roblyn writes of a photo going “live” in her iPhone’s library. Her late husband sits masked for his chemotherapy infusion when his head nods, and eyes rise to lock with hers, a digital cruelty.

The zoomed image of my mother is magnetic in another way. She sits with her hands in the pockets of a long coat before the old cathedral’s derelict wall. Expanding the image, I feel her genuine happiness, what I’d longed to capture and hold onto in my childhood.

My mother happy was generous and forgiving.

How strange that she is also just some woman on a postcard. You can’t see what I see, just as Mary Roblyn’s husband’s eyes would not cut through me.

Each of us accumulates and carries vulnerabilities, soft underbellies, peeled scabs, parts invisibly chaffing.

How is it we believe we can know each other at all? Increasingly weighted, we move through time and space, awkwardly introducing ourselves. The older we are, the more difficult it seems to answer, How are you?

(Easier to stay home and watch postcards grow legs to walk off the end table.)

Some women are silent at the end. Or talk incessantly and incoherently, as my mother sometimes did. Or stare wide-eyed from within their ever-shrinking selves and vast interiors. Are they disdainful or awestruck?

There may be no one left to tell. No one who sees what they see, knows who they knew, or knew them like they do.

My mother made a self-portrait at age 22 that carried a cathedral of a story. “Woman in Black” is the story of that haunting print intaglio …

I wish I knew who wrote or said this; please leave a comment if you know.

I love this because I love postcards, still send them, and I am incidentally currently busy deciphering postcards my grandfather sent from WWI while serving in the Austro-Hungarian army. I had a similar experience as yours in that one of those postcards shows his regiment, and only upon magnifying it did I realize my grandfather was in it and had, in fact, drawn a tiny arrow pointing at himself. I would hardly have recognized him as a gaunt young man in uniform. Thankfully, I've got dates on those postcards, either he dated them writing to his brother, also serving in the military at the time, or there's the oh-so-helpful postmark. Alas, the images shown on the other side of those vanity cards? Many of them are a puzzle! In any case, what a startling and ultimately precious find this postcard is for you!

Eliza! I can feel the shock of seeing your mom here, so unexpectedly. It is a message from another world. I’m glad that you saw a different person from the one you remember. It gives us hope to find the small things that fill out the complex whole that is a human life.

I’m honored that you referenced my post. Thank you for your lovely comments. Grief isn’t simply a single emotion. It surprises us by feeling sometimes like deep sadness, and sometimes like joy. Much gratitude for sharing your experience.