Art and the Families

I found letters from the painter Marcia Marcus in my mother’s loft. Then I found this painting of Marcia’s online.

Two Houses is a newsletter of stories about art, feminism, grief, and Time excavated from the Soho loft where I grew up. Posts are free and illustrated with the work of my long-divorced parents, the painters Mimi Weisbord and Lennart Anderson.

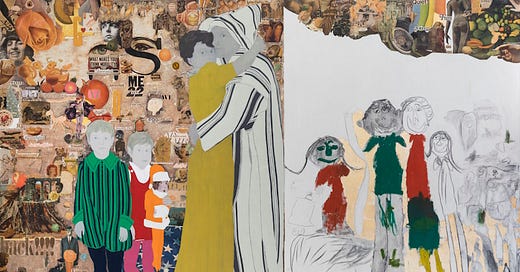

Art and the Family nearly shot me between the eyes when I saw it. Almost half the picture is joyously taken over by the painter’s young daughters.

The artist shares her canvas. Her children take up space! (My child-self erupts.)

On one side, the picture holds an elegant family portrait backdropped by a dizzying collage of magazine images and news-clipped words (e.g., “family security,” “ego,” “your wife,” “the endless war.”). On the other side, her children’s exuberant family portrait pushes up against that curtain of 60s social, cultural, and political noise like wildflowers cracking pavement.

Once, my brother and I drew balloon-headed crayon people on the walls of our bedrooms in Brooklyn. But I don’t recall a single instance of drawing our family together, never mind on a parent’s canvas. My mother, Mimi, left my father, Lennart, in 1972; we lived between them in their divorce’s dark crevasse.

On Marcia’s canvas, the collage ends abruptly at a jagged edge. The children’s family portrait disrupts the rhythm of their mother’s work and the cacophony of the adult world. Here is competition between family, artmaking, and the noise that surrounds them.

Yet their drawing is a full-throated response to a carefully orchestrated invitation from the artist, their mother.

Created in 1966, Art and the Family is Marcia Marcus's largest painting, and it spotlights the context of a woman artist. Yet it’s also a kind of Rorschach test for anyone who grew up in that era. For me, the daughter of divorced painters, Art and the Family is prescient. The turbulence of the times is about to land squarely in American living rooms.

This is a monumentally important work.

By 1969, the Women’s Movement erupts with consciousness-raising groups all over New York City. Families split apart as women seek a path for their own ambitions (my mother included). Centered on this canvas, the adults hold onto one another against the torn backdrop of social tumult.

The family takes center stage just as it is about to be upended.

I found a moment in my mother’s journal where Lennart responds to Mimi's desire for children. “I’m afraid I won’t want to be so much of an artist,” he says. What does that even mean? She asks.

Even before conception, we were their never-ending negotiation.

I’m learning about Marcia through her letters to my parents, through the documentary film Art and the Family, and in conversations and emails exchanged with Marcia’s daughters, Kate Prendergast and Jane Barrell Yadav. We’ve shared letters, artifacts, and histories as daughters of painters and of women artists. I’m following these breadcrumbs to understand the context of my parents' early relationship, which blooms art-historical from the material world my mother left behind, seeding the central drama of my childhood and psyche: the bitter divorce of the painters who made me.

When the Women’s Movement arrives, Marcia is mid-career. She does not need consciousness-raising to find her North Star. Her art ego is solid.

My mother’s is not.

“The art world is Lennart’s,” Mimi laments to her psychoanalyst in her journal the year she left my father.

“Who gave it to him?,” her analyst responds.

Marcia would never have given up the art world.

Marcia is seven years older than Mimi, and by the time they meet, she has already annulled a first marriage because her husband doesn’t support her attending art classes at the Cooper Union. She takes temp jobs in offices and unemployment whenever she has the chance. While my parents are in Rome, she marries her second husband, Terrence Barrell, who is also an artist but the rare bird ready to take a back seat and play a primary role in raising Jane and Kate. (He was the eldest of five.) Marcia can have both children and an art career.

She paints each summer in a Provincetown dune shack where she can ignore her children as Terry chases them feral in the sand. She embraces the chaos of her ambition and inspirations.

In a letter to my parents dated 1961, Marcia has a one-year-old, is pregnant, and is planning a self-funded trip to Italy and Greece.1 Thus far, Marcia has not had success with prizes or fellowships (She wins one the following year.), but Lennart and other painters they know have fellowships to Rome, Florence, Paris … everyone, it seems, has headed to Europe.

Prize or no prize, Marcia is going, too.

Her chutzpah is dazzling.

“As usual, leaving with enough [$] for about a month’s living and hoping for best. See - nothing changes me,” she writes of her plans despite her pregnancy.

She embarks alone with Jane and drives all over Italy to the sites recommended by Mimi and Lennart, finally settling outside of Florence near friends from New York, the painters Bob Beauchamps, Red Grooms, and Mimi Gross. She leaves Jane with kindly strangers to dash unencumbered into museums (Mimi Gross has told Jane). She gives birth to Kate, aided by a traveling midwife (by then, Terry has joined her), and paints until her contractions are three minutes apart. She is working on a huge painting of Red Grooms that she returns to immediately postpartum.

“TRY FIND GOOD USED CAR PREFER MAY BE BUS LOVE = MARCIA =” She telegrams Mimi and Lennart for help before setting off.

Marcia follows her bliss.

Growing up, I knew Marcia Marcus only as a friend and admirer of my father’s. I did not know she’d also known Mimi. I did not know she was even an artist. To Kate and Jane, I recalled spending July 4th, 1976, at Marcia’s high-rise apartment waiting for the bicentennial fireworks. I was nine. There was no evidence of a studio. No smell of turpentine.

Kate explained that their mother used their living room as a studio and cleaned up for the party. “I grew up with no living room,” she says she’d tell her therapist (double entendre intended) in the years she was coming to terms with her mother’s priorities.

***

Mimi was also a force of nature. She was an ardent feminist who fiercely embraced her artist identity. But I’ve learned since her death that she didn’t start out that way. Phyllis Tower, Mimi’s roommate from 1958, describes her as fragile, as a young person who did not yet take herself seriously as an artist, and as madly in love with my father.

In “Woman in Black,” I explain discovering my mother’s stunning success in the months leading up to my parents’ wedding—a moment of fame as an artist that did not come again in her lifetime. Phyllis has emphasized to me how few lanes were then open to a woman artist. “But the Artist Wife, they were everywhere.” (Phyllis married and divorced the painter Edward Lazansky.)

I get that. I see it. I do. I even stitch it to the way my mother used to ruefully laugh at retro ‘50s fridge magnets: “Marry the Man You Want to Be!”

But now I see, too, that when my mother moved to New York City for her art school fellowship, she was—thanks to Lennart—swiftly surrounded by ambitious women painters. They were seven and eight years older, my mother just 22. It must have been intoxicating.

So, while there was little opportunity for a woman artist in that era, my mother knew women who gritted it out.

“I am still in the March gallery,” Pat Passlof (the abstract expressionist) wrote Lennart in 1959. Pat was one of the few women artists to achieve attention and respect in that era. (My father knew her from Cranbrook Academy.) “I get into all the new talent shows around town; chances are good that I will have a gallery within the next year or so. I sold 3 or 4 small things this year which is a triumph for me but a drop in the bucket to anyone else.”

Lois Dodd, a figurative painter and a founder of the (now-fabled) Tanager Gallery, writes in 1961: “My show closes tomorrow. I sold one painting but altogether this has been a very poor year for sales or even enthusiasm.” Lois spent a year in Rome with my parents on a grant from the Italian government.

In her journal, Mimi imagines her path not taken (a passage I also quote in “Woman in Black”):

“Suppose I hadn't married L. but let him go to Rome while I stayed on in New York [...] I could have hung out downtown with the people I already met and showed a painting or two at the March Gallery. Gone to shows & the artists' club […] It would have been great if I could have gotten a part-time job to support myself with—and taken myself seriously as a responsible person and an artist.”

Both Marcia and Pat showed work at the March and attended the Artists’ Club.

Marcia’s letters, life, and choices help reframe the early Mimi for me. The bitterness that thrummed through my mother had points of origin. She married just as her work gained attention. She wrote in her journal: “I went to Rome an artist and came back a wife.”

My uncle once said Mimi regretted giving so much of herself to the Women’s Movement. I didn't believe it, but now I see why she may have come to feel that way. The Women’s Movement provided a critical lens for the 50s role she’d bought into and offered respect for wanting both children and an art career. But she knew women who hadn’t needed that bolstering. They had just kept painting. They’d bushwacked their own path, navigating the obstacles and wider culture to have long careers. My mother didn’t regret the Women’s Movement; she regretted needing it so badly.

In 1977, Mimi wrote an article for Women Artists News covering a panel of “Women Artists of the ‘Fifties.” The panelists were Ann Arnold, Louise Bourgeois, Gretna Campbell, Marisol, Marcia Marcus, and Pat Passlof.

“‘In the 50s, I felt that I really became a painter,’” she quotes Marcia. “‘I never felt discriminated against because I had the feeling that, for whatever reason, I had every right to be there ….’”

“‘I thought of myself as a struggling young artist—never felt I was persecuted,’” Ann Arnold weighs in. “‘[….] But an artist has so many problems besides those of being a woman…’”

Pat Passlof felt she misunderstood the slights against her, “‘If you’re a young artist whose work is just developing and someone looks down on you, it isn’t clear it’s because you are a woman … you could just as easily think the person doesn’t like your work.’”

Louise Bourgeois: “‘Yes, it’s very difficult, but I happen to like a good fight.’”2

***

In 2017, Art and the Family was shown at the Firestone Gallery. In “Marcia Marcus, Role Play: Paintings 1958 – 1973,” art critic John Yau reviewed the show for Hyperallergic, calling Marcia “a forerunner who has not received the recognition she deserves. [….] Her work addresses a wide range of formal and social issues directly and indirectly. She is the forerunner of Catherine Murphy and the melding together of direct observation and the imagination. Someone should really do a book on her.”3

As happens, it’s now up to Jane and Kate to archive and promote Marcia’s work—a huge challenge and responsibility; Marcia deserves recognition for her place in American art history.

I dodged a bullet that my mother didn’t lay more groundwork or gain the traction that Marcia has with paintings in major museums and a yet-to-be-appreciated influence. As difficult as it’s been on both a material and existential level to inherit Mimi’s work, it doesn’t carry a sense of urgency.

And so, for now, I can enjoy and plumb Mimi and Marcia’s art and history and the way our broken families intersect.

Marcia and Terry also split apart in 1972.

Yet on this huge canvas, their family remains together, preserved in a moment in time to transcend it. Art and the Family spotlights the family of a woman artist who dared raise children within the creative and social chaos—a precarious celebration that remains hauntingly relevant. In 2024, artists (and writers) of all genders struggle to create within and against the roaring context of a frightening wider world. We also seek ways to give our children voice and agency (and succeed and fail) in a challenging era.

I didn’t know Kate and Jane growing up, but finding our mutual histories and overlapping concerns, I join them on this picture plane where they break through shimmering, exuberant, disruptive, also their parents’ creation, also a work of art.

Art and the Family may be viewed by appointment in St. Louis, MO at The Horseman Foundation. Email: info@thehorsemanfoundation.org

Related posts: Woman in Black, Susan’s Portrait, Mimi’s Pompeian Mural

She is partially sponsored by a collector.

Mimi Weisbord, et al. “Women Artists Newsletter.” Women Artists Newsletter, vol. 3, no. 2, June 1977. Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University. Independent Voices. Reveal Digital, JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.28046882. Accessed 16 June 2024.

Yau, John. “A Cerebral Portraitist‘s Unaccountable Neglect.” Hyperallergic, 29 Oct. 2017, hyperallergic.com/407992/marcia-marcus-role-play-paintings-1958-1973-eric-firestone-gallery-2017/. Accessed 16 June 2024.

You weave together so many threads here. That comment about going to Rome as an artist and returning as a wife is so poignant. But you also show the many different paths people were able to carve for themselves (the machete!).

The painting so nicely frames this essay. How interesting to find company with Marcia's daughters now. It is as if you are repainting the portrait you had of your mother as you discover parts of her you hadn't known as her child.