Two Houses is a newsletter of stories about art, feminism, grief, and Time excavated from the Soho loft where I grew up. Posts are free and illustrated with the work of my long-divorced parents, the painters Mimi Weisbord and Lennart Anderson.

KATE Larkin and I first introduced our mothers as a consequence of our friendship formed at the Park Slope Community Nursery School. The year was 1970. Kate enthralled me with her long red hair; she looked much closer to Marcia Brady than I did with my head of dark curls. In her room after school, we’d play Barbies and make Easy Bake Oven mixes. My mother did not want me to have those toys, so they were pleasurable contraband (Barbie’s breasts nipple-less and mysterious). My dollhouse entered our house only as a Christmas present for my brother. (I had been gifted a stethoscope that year but ended up commandeering both.)

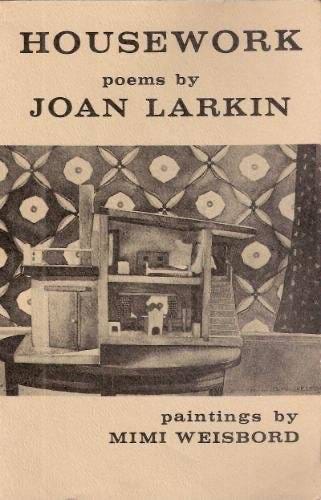

In 1970, women throughout New York City were gathering in consciousness-raising groups to tell the truth of their lives and find new possibilities for themselves and their daughters. Joan Larkin credits my mother, Mimi Weisbord, with recruiting her to the Women’s Movement. Mimi’s paintings of my dollhouse illustrate Joan’s first book of poetry, Housework (Out and Out Books, 1975).

Joan was already divorced and a serious poet by the time she met Mimi. Various poems in Housework were originally published in places like The Village Voice and The Paris Review. Mimi, on the other hand, had turned her back on an art career in the ‘60s, attempting to live through her husband’s. When she met Joan, she was producing feminist arts programming for WBAI-FM. “Women Poets Reading” became her platform for broadcasting emerging and established feminist poets, a separate lane of interest from her husband’s art world. It’s easy to see why her friendship with Joan was intense. Joan went on to produce programming for WBAI, too.

In 1972, Mimi left my father (Lennart Anderson) and, within a few years, returned to oil painting. Her first solo show was at Prince Street Gallery and featured her dollhouse paintings and a book launch party for Housework.

In 2020, during Mimi’s Zoom memorial, Joan held up a charcoal study for a dollhouse-with-fireplace painting, a gift to her from Mimi. She spoke of how it suggested to her Mimi’s enduring passion, her burning inner life.

I loved that.

But in my writing, I’ve wondered if it was my mother’s passion or her rage.

“HOUSEWORK,”1 the volume’s title poem, reminds me of that quandary.

In the poem, a woman is killing flies in a kitchen with a rolled-up magazine. (“I live by insisting on my hatreds.”) Outside, the world is saturated in rain (“houses made of rain.”).

One fly seems a goad, a reminder of the unhappiness that simmers when passions go untended, when “the life force” washes away in the rain of forgetting.

I forget what I wanted. Was it old music laying gold-leaf on the evening? lamplight sweetening the carpet like honey from Crete? a dream of/door to Egypt? Something to do with the life force.

The poem ends with, “There is a fly in this house that will not die.”

My mother left our house where she felt she was suffocating. Leaving wasn’t easy, but leaving was necessary and had “something to do with the life force” (a line I swear I can hear her say). She left for a difficult life as an artist. And as a parent.

It’s a complicated legacy, this “rhyme of my inheritance” (to echo another of Joan’s poems). To be the daughter of this dollhouse of passion and rage, with so much to gain from the Women’s Movement and so much to lose when she moved out with every bed and most of the dishes and cookware. My brother and I spent one weekday and every other weekend with our father in our emptied-out house. Lennart was not quick to replace anything. For a time, after the split, we slept in his studio with St. Mark’s Place. (In early iterations, the woman on the stairs held a knife in her hand.)

AT THE end of her life, my mother was churning with dementia, frustrated with her limitations, revisiting old wounds, and excoriating me with rage. In the midst of this chaos, I reached out to Joan. She had by then lost touch with Mimi; we had not spoken in decades. I was grieving my mother’s mind, and her dignity lost to the insults of the memory care residence I’d had to move her. I needed to talk with someone who knew who my mother really was. (I needed to confess what I’d done.)

Joan called back, full of love and compassion. She was at MacDowell. I felt overwhelming joy and relief to find her well and still writing. I also felt a kind of (unearned) kinship. I was coping with my mother's chaos by writing uncontrollably.

In the end, at the very end, it was no surprise to anyone that my mother had a hard time letting go of the life force. She’d developed the habit of the battle. After she knew what she wanted and had lived well, she insisted on her passions as well as her hatreds. She was a force of nature whose complex gifts I’m still unpacking.

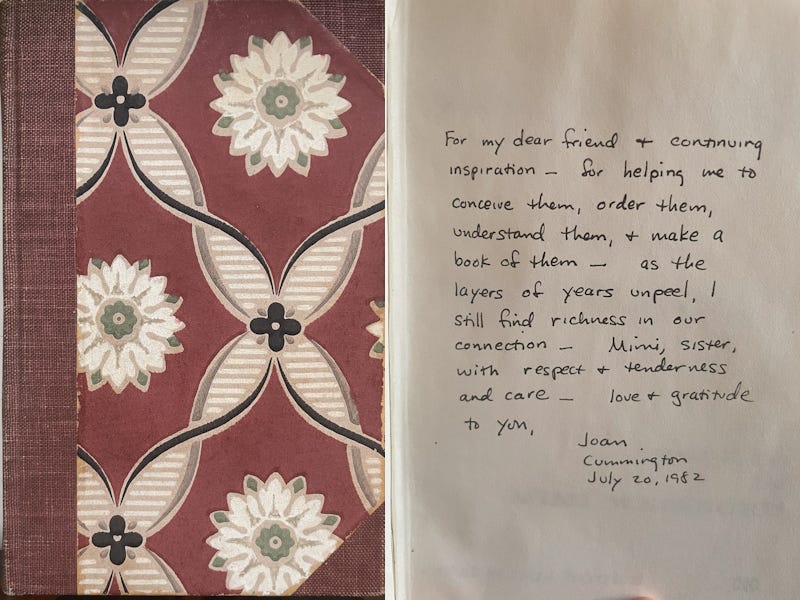

Found in her loft was a hardcover volume of Housework. She’d hand-bound it, using wallpaper for cover art salvaged from the colonial-era farmhouse we’d had for a time in Western Massachusetts. Several of the dollhouse paintings were made there. Joan inscribed this volume in 1982 when she and Mimi were at the same summer art colony in Cummington, Massachusetts.

Adrienne Rich reviewed Housework in Ms. magazine in 1976 (an edition I’ve lost among the piles, sadly). Lines from Rich’s “Diving Into the Wreck” serve as a kind of guidepost for my writing, for surviving my mother’s passage, and the excavation of her loft left behind:

“I came to see the damage that was done/ and the treasures that prevail.”

Joan’s poem, this volume — a treasure, truly.

“Housework”

(reproduced with permission)

for M. W. Through this window, thin rivers glaze a steep roof. Rain: a church of rain, a sky--opaque pearl, branches gemmed with rain, houses made of rain. I am in the kitchen killing flies against the cabinets with a rolled-up magazine, no Buddhist-- I live by insisting on my hatreds. I hate these flies. With a restless wounding buzz they settle on the fruit, the wall--again, again invading my house of rain. Their feelers, like hard black hairs, test the air, or my gaze. I find I am praying Stand still for me. I'll devil the life out of you. The human swarm comes in with wet leaves on their sticky boots. They settle on me with their needs; I am not [nice. Outside, headlights of dark cars are winding the [street. The mirror over the sink will do me in. At five o'clock, rain done with, in darkness the houses gather. In the livingrooms Batman bluely flickers; the children all shut up, all but an angry baby or a husband. The suburb is wreathed in wet leaves. I forget what I wanted. Was it old music laying gold-leaf on the evening? lamplight sweetening the carpet like honey from Crete? a dream of/door to Egypt? Something to do with the life force. December turns the sky to metal, the leaves to gutter-paper. Leak stopped, the bedroom ceiling starts to dry. Its skin of paint is split and curling downward. There is a fly in this house that will not die.

Joan Larkin is the recipient of numerous awards and honors, including two Lambda Literary Awards and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the American Academy of Poets. Her seventh volume of poetry, Old Stranger: Poems, is forthcoming from Alice James Books.

Housework (Out & Out Books, 1975), reprinted in My Body: New and Selected Poems (Hanging Loose Press, 2007), Copyright © 1975 and 2007 by Joan Larkin.

Eliza Anderson you are an amazing writer and will put Vermont on the map someday!!

Lovely writing, and a beautiful poem.