Life and Death in the Studio With Lennart Anderson

I found a YouTube clip of my late father mixing paint

Two Houses. Two Painters. Two Parents. is a newsletter of stories about art, feminism, grief, and time excavated from the Soho loft where I grew up. Posts are free and illustrated with the work of my long-divorced parents, the painters Mimi Weisbord and Lennart Anderson.

After I published my essay last week, I found a YouTube clip of my late father working on the large painting Jupiter and Antiope, the subject of that post. For a moment, I wondered if, playing it, I would hear him say this painting had to do with the passing of his second wife (Barbara). I had racked my mind trying to decide if that memory was from a time with him in his studio or from watching a video of him. He’d said it, I wrote, unaware I was paying attention, and I knew that much was true; I had a strong sense I’d overheard it. But am I a viewer like any of the 1.9 thousand views of this video? Or am I his daughter as he speaks with a studio visitor (such as David Marshall, who shot that blurry clip in the era of flip phones)? It’s a strange, disorienting feeling not to be sure.

It reminds me of a sensation I had when I tried to record him telling one of his art theft stories; he dropped his warmth and spoke formally as though I were not his daughter. I felt a cavern open between us. He wasn’t talking to me.

It was frustrating on several levels, but mostly because I wasn’t after the story of a stolen painting as much as his hilarious storytelling. I wasn’t interested in hearing from the master painter; I wanted Dad. I was unaware that a video of his mixing paint would someday garner 1.9 thousand views. I didn’t know until his death the depth of his modest following.

Yet, now it feels normal to find him alive and talking online. Isn’t it common to feel like we can pick up the phone and call our late parents? How long does that last? It’s faded, I realize, writing here.

Still, it seems natural that he continues mixing paint in the digital ether. Increasingly, I think that’s where we’re all headed. Once, it may have been heaven, but now it’s the Cloud. He’s waiting for me there, gripping his palette knife.

I’m gripping a lot these days. My toes are often curled; I suspect this is how I wrecked my left foot, which needs surgery, I fear, because I’ve been gripping for years.

Here is my thumb gripping a paintbox I came across while cleaning out my mother’s SoHo studio in 2021. I felt clever figuring out how it was meant to be held.

That box must be from the 1960s. I never knew my mother as a landscape painter working with oils en plein air. But after her death, I found a stack of very small paintings from the early years of her marriage when they sometimes painted together. Here is an iPhone photo of one of these that is so much like a Lennart Anderson that I cannot be sure who made it.

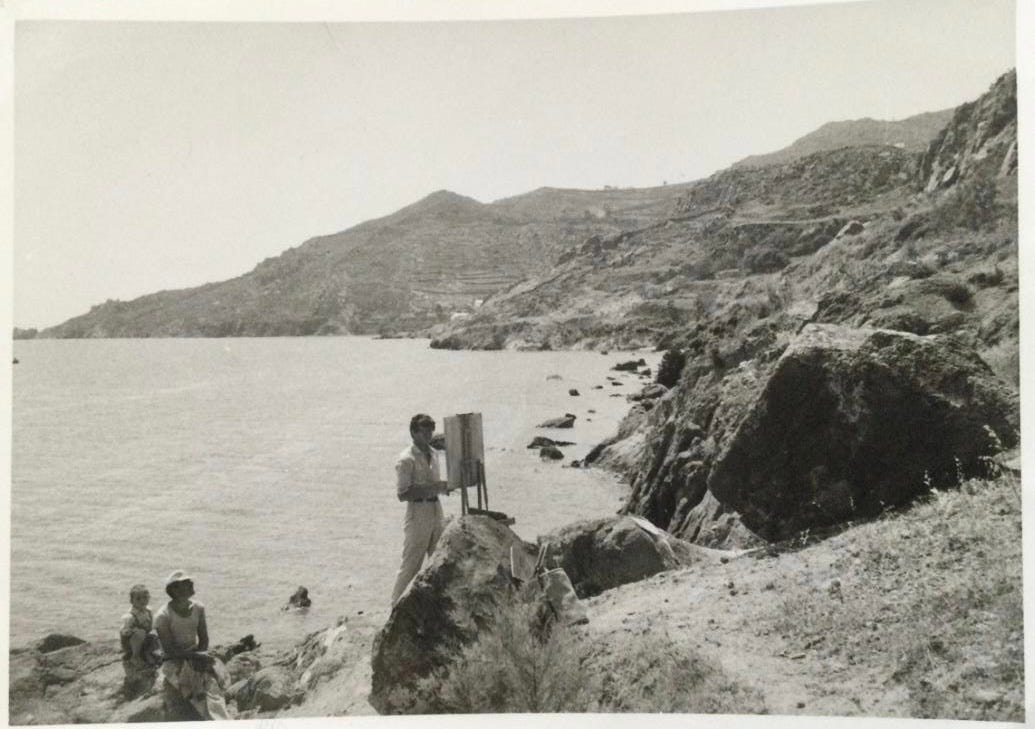

I still have my father’s paintbox/easel for landscape painting. I found it tucked in a corner of the camp he had in Maine. It’s very old and speckled in paint, and it dawned on me all in a rush that, just like his leather belt, he’d had the same one all his life. I’m sure it’s the same easel as in the black-and-white picture from Greece that I found in my mother’s letters from 1959. I’m certain he’s also got on that familiar belt.

I knew the belt well because, for a while, I came up to his waist. And before that, I’d hold his hands and walk up his legs to his chest to do a backflip to the floor. I’d find him talking to someone in his studio and start climbing as he held my hands and kept talking. Eventually, I was too big, but back then, there was so much ahead, and he was still there, and I didn’t see it as Time passing: the phenomenon that would take him and wreck my foot. The other reason I knew his belt well was because, for years, I’d watch TV with my head in his lap on the couch. He smelled like paint and leather and corduroy and the fig and cheese he was eating or a Bosc pear. He ate the subject matter that he often painted.

Kim recently picked the first pears off our small fruit trees, and they are stubborn like him with no plans to ripen. They make me miss him because he would have painted them if it were time for a break from the insufferable large picture he refused to finish, back when Time seemed lavish, expansive.

Honestly, I don’t understand the draw of this blurry YouTube video. It does not record much about that painting (that memory is mine alone). Why would it have 1.9 thousand views? Is it because he’s painting while losing his eyesight? Is it because he sees no difference between paint properties and his own (failing) perception? There’s this moment at minute 1:30 that seems to record his stubborn insistence that what he sees is what is there. And then it slips into acquiescence to the possibility that’s not the case. I’m not sure he knew he was being recorded.

LA: That's what I really miss, that I can't mix the ochre with black and get anything that looks greenish.

DM: Because you can't see it.

LA: It just doesn't make it. It isn't there!

DM: [Silence]

LA: This color does not mix with black and make green. It makes... [well] you have to call it that.

DM: Yeah.

LA: It's as green as you can get.

He was furious when I told him he should wait for his cataract surgery before continuing to work on his big picture (then Idyll III, not Jupiter and Antiope). He did not want to hear that the colors he saw were not true. I was alarmed to see bright colors landing on that painting that he otherwise rarely used.

My mother was incredulous when I mentioned the problem on a visit to her in Manhattan. “But he knows the colors in those tubes!,” she said with exasperation.

I couldn’t explain it other than that he insisted on his perception over everything else. He knew his eyes were failing (first to cataracts and then to macular degeneration). He knows it in this video. Yet there’s slippage between that admission and blaming a change in the paint. (Maybe both were true?)

In the hours before his death, he told me that his arm had begun to hurt from an old injury.

That injury was flaring, he worked to explain, his voice suddenly full of gravel as he lay in his hospice hospital bed in his living room in Brooklyn. He knew he was dying.

Heart in throat, I responded breezily, How about we try a little morphine?

He blamed his tennis elbow, yet his sober nod suggested he understood more.

(In hindsight, the pain must have been terrible. My father’s pain tolerance was so high he’d get his teeth drilled without Novocaine.)

I wish I’d known we had maybe an hour. There’s always more to say. Certainly, I won’t find this memory on YouTube. Recording it here, I’m expanding the record of his character. Stubbornly, I’m filling gaps for him and for me. And I know I am his daughter.

Joan Larkin’s latest volume, Old Stranger: Poems, is now available from Alice James Books. Last week, I enjoyed live-streaming her reading at a bookshop in Brooklyn. A poem of hers likely worked in the back of my mind to influence this post. She reads “My Father’s Tie Rack” at minute 3:21:

(Work by my mother, Mimi Weisbord, illustrates Joan Larkin’s first volume of poetry, Housework. I wrote about that and the title poem, which she dedicated to her in that volume, in “Housework - A Personal History.”)

This one moved me to tears. Maybe because my mom also had macular (although she certainly wasn't an artist). Maybe because of how you captured the fleeting nature of time.

How fascinating to find the video of your father after his death. And your explanation of what was happening to him at the time with his own vision made me feel an unusual tenderness toward him as an artist (rather than a father). And I found myself watching more videos about him.... and seeing through a daughter's eyes.