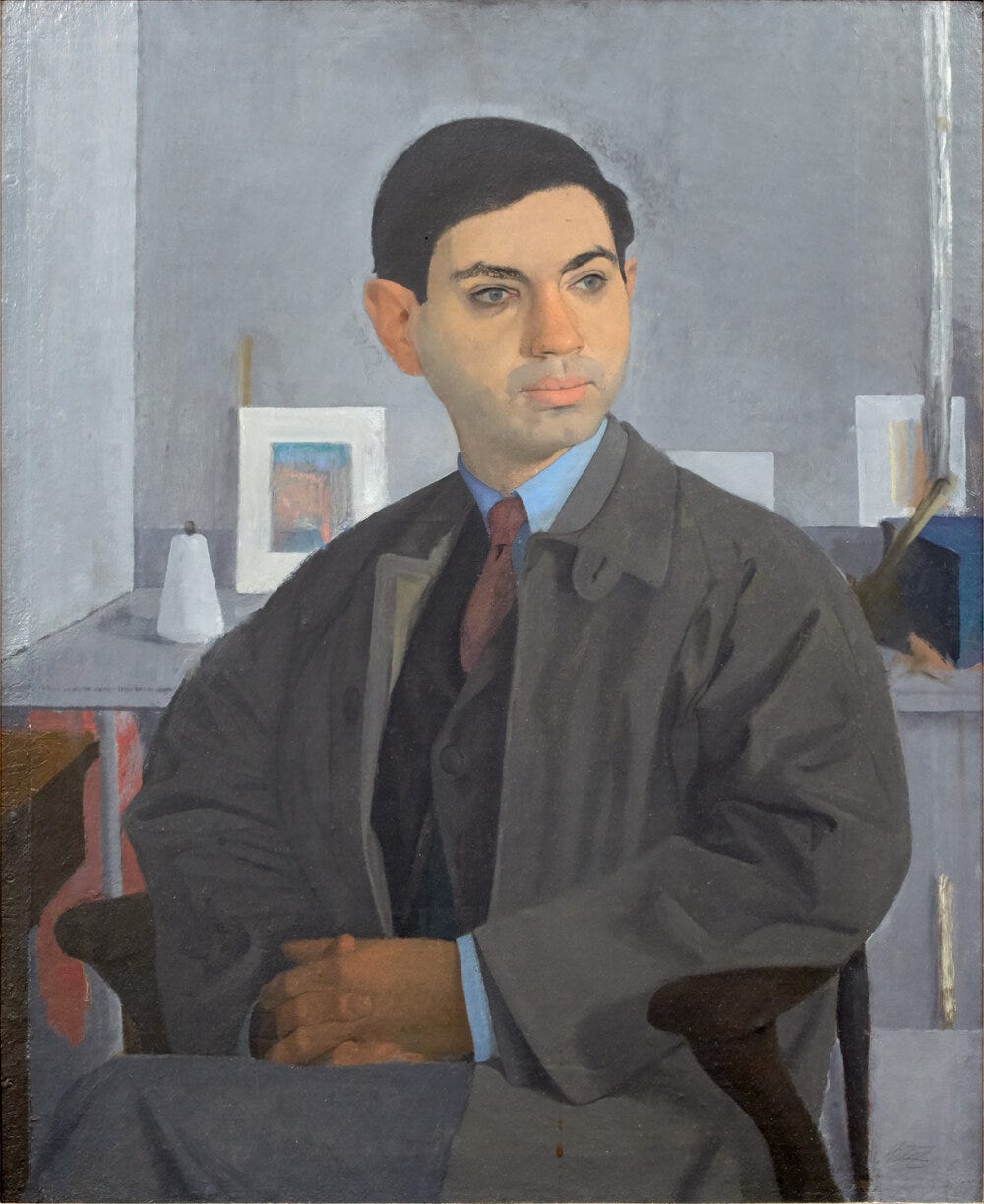

Two Houses. Two Painters. Two Parents. is a newsletter of stories about art, feminism, grief, and time excavated from the Soho loft where I grew up. Posts are free and illustrated with the work of my long-divorced parents, the painters Mimi Weisbord and Lennart Anderson. Sign up here:

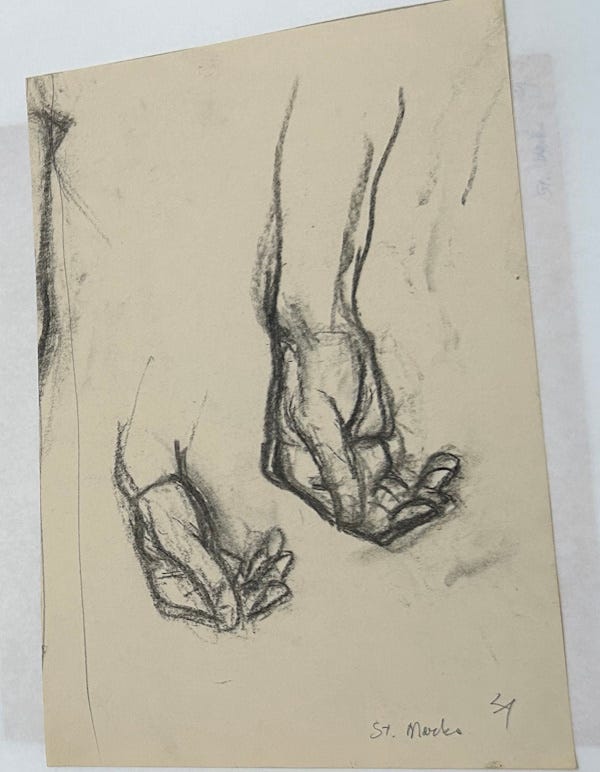

My father had a long scar between his thumb and forefinger. A blade went straight into the meat of his hand. He had large hands (like mine; my piano teacher marveled that I could reach an octave and two). Elegant with long fingers, they were, nevertheless, working hands — rubbed vigorously with the abrasive grains of Boraxo powdered hand soap after painting in his studio. The scent of Boraxo greeted me at the door after school. In the evenings, on the couch watching TV, I would trace that white jagged line extending from the soft web of his double-jointed thumb.

He’d tell the story of that scar as part of his repertoire of reasons he was a painter.

As proof he was capable of nothing else.

When he came to New York to pursue an art career in the early 50s, he failed at first to find a way to make a living. He was about to head home to Detroit with his tail between his legs, but first, he tried to get a gallery for his work.

One dealer, Roy Davis, was impressed with his paintings but not ready to represent him. Instead, he got him a job at Bob Kulicke’s frame shop so he’d stay in the city. That’s where my father ran the blade of a power jigsaw straight into his hand.

An emergency room team stitched him up and sent him home taped and bandaged. But instead of going home, he returned to the frame shop.

I don’t recall if my father ever said why he did that — if there was work he needed to finish, didn’t want to let down his new employer, or didn’t want to feel like a quitter. But when he first came to the city, he took a holiday-season sales position at Lord and Taylor; he described the swarm of shoppers and the streams of curling register tape that trailed after him as he marched a straight line through the crowd and out onto the street, never to look back.

Since he’d already walked out on one job, I imagine he returned to the frame shop to prove himself. Certainly, he had a remarkable tolerance for pain. He would get his teeth drilled without Novocain.

Back at Kulicke’s, however, injured and, likely, rattled, he immediately ran that blade through his bandages, blowing open the same spot in his hand. That emergency room team got to stitch him up all over again.

Bob Kulicke was also a painter. And he was sympathetic when, eventually, Lennart asked to get laid off so he could paint on unemployment.

What was it like for my father to carry that scar around for the rest of his life? Lately, I wonder.

In Woman in Black, I wrote about uncovering a festering wound carried by my mother. She’d left New York to marry my father just as her art was attracting attention. What wounds did Lennart carry?

In the 50s, men whose tools were paint brushes or, at most, a palette knife contended with suspicions about their manhood. My father’s gentle, affable nature likely didn’t help. Or that he had no war record.

He’d been too young for WW2 and was rejected for Korea. The draft board’s psychologist had told him directly, “We don’t need artists in the army.”

Lennart didn’t want to go to war, but I’ve come to understand the rejection bothered him. He’d not made the grade. He knew he could do nothing but paint, and the government confirmed it.

One of the artists Lennart moved to New York City with was Ruben Eshkanian. Ruben was a weaver and fabric artist Lennart knew from Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan.

In 1990, when I came out as a lesbian, Lennart told me that Ruben had, more or less, lunged for him in their room on their first night in the city.

Ruben and Lennart’s friendship survived the misunderstanding.

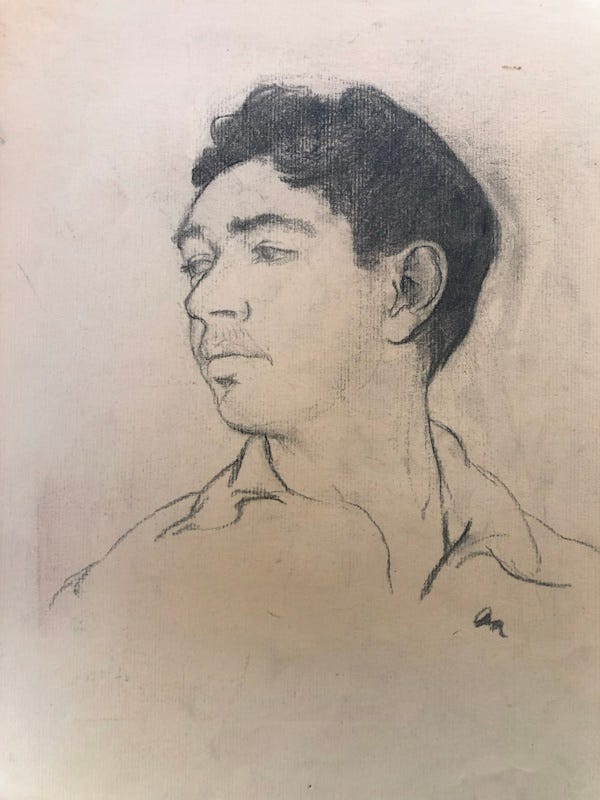

My father made various drawings and portraits of Ruben in the 50s.

They remained lifelong friends.

Did my father remember that scar on his hand when he’d tell me to be careful?

After I suffered some calamity, he’d always warn me to take special care. He’d say sometimes bad things roll one to the next. It didn’t occur to me that he was speaking from personal experience.

Now, I’m working on admiring his single-minded sense of purpose. Isn’t achieving a sense of “mastery and flow” what we aspire to and a cornerstone of happiness?

Recently, I learned that Bob Kulicke hired another painter for his frame shop in the 60s. Earle Olsen must have had great skill with the jigsaw. He worked for Kulicke for many years.

I learned of Earle when I stumbled across From Life with Victoria Olsen, his daughter’s substack. I was astonished to find her this way.

We connected, and she told me our fathers had known each other, that she’d spoken with my sister, and even attended the Lennart Anderson retrospective at the New York Studio School in 2021.

It turns out that Lennart and Earle had a lot in common. In addition to both working for Kulicke, they’d both studied at the Art Institute of Chicago (not the same years; Earle was older), and both have paintings in the Whitney Museum’s collection.

Earle, however, was drafted (though he never went overseas).

Like me, Victoria has been digging into her father’s history and her childhood “origin story” of her parents’ divorce. In “Secrets and Lies,” a post that excerpts her memoir, she writes: “My sisters and I grew up with the sense that art was our rival.” In 1970, Earle left his marriage to focus on his art career.

Or so he said.

Reproduced at her post is an amazing work of art by Earle.

Gagged depicts a man’s gagged head made of a perfect tangle of anxious continuous lines surrounding eyes shot through with palpable desperation.

Earle — Victoria would find out years after her parents separated — was gay.

Learning of Earle made me think of Ruben. And what it must have been like to be gay in the 50s, a time of so much repression, ridicule, and risk. I imagine Ruben was terrified and hopeful in that hotel room with Lennart on the first night of their new life in the city. They must have both been fearful for different and yet similar reasons.

Trapped as they were with their passions.

Thank you for this beautiful story. And Lennarts work is masterful and beautiful. I imagine you are familiar with "Night Studio" written by Musa Mayer the daughter of artist Philip Guston?

Wonderful that you are able to join these dots, Eliza. Earle's artwork, "gagged", is so startling. And I love your father's portrait of Ruben.